We all know that chlorine is a toxic chemical. That’s why we use it to kill harmful microbes in drinking water, but we don’t want to chlorinate to kill aquatic life in our lakes and rivers or have them smelling like public swimming pools devoid of life. During normal operations, water utilities regularly discharge small amounts of water with low chlorine and chloramine concentrations, such as during flushing and hydrant flow testing. AWWA addresses these discharges through Standard C655 – Field Dechlorination. Large spills of chlorinated water due to large pipe breaks or fires are emergency situations that are not covered in C655.

Standard C655 divides disinfectant releases into two categories: high (>4 mg/L) and low (<4 mg/L). High levels, usually associated with disinfecting new mains, usually require chemical dechlorination using some reducing chemical, such as sodium bisulfite, which strips chlorine and oxygen from the water and poses some risk to aquatic life.

This blog is about discharges of drinking water used for maintenance such as flushing and flow tests. These uses only release a small amount of chlorinated water over a short period of time.

The standard defines two types of dechlorination―chemical and nonchemical―and it encourages operators to use chemical methods by making it difficult to justify nonchemical methods.

It only acknowledges the following six types of nonchemical methods:

- Holding tanks

- Land application

- Groundwater recharge

- Natural obstructions (e.g., hay bales)

- Storm sewers (if dechlorination is tested)

- Sanitary sewers

These methods sound reasonable, but there are two other considerations that are omitted: dilution and rapid reaction.

Dilution. Consider flowing a hydrant at 500 gpm into the Mississippi River or the Atlantic Ocean. You would not be able to find any chlorine after about a second of dilution. Such mixing, however, happens after what the standard calls “loss of control” and is not considered acceptable in the Standard.

Rapid reaction. If receiving waters were comprised of distilled water, you would expect the disinfectant to persist for a long time because there is nothing with which to react. However, real water contains a wide range of chemicals and physical materials that react with the disinfectant at varying rates. Many times, the disinfectant will disappear almost instantly as there is a surplus of these species. In other water bodies, when there is a low concentration of such species that react with chlorine or chloramine, breakdown can be slow.

The standard fails to acknowledge either dilution or reaction.

I have been involved in two studies (Walski, Helsel, Strickland, Whitman, 2013; Walski, Helsel, Strickland, Whitman, 2015; Walski, Whitman, Douglas, Casey, 2019) that show that dilution or reaction with travel time can eliminate the need for chemical dechlorination. In the work that we did, we conducted benchtop tests looking at decay rates in a variety of receiving waters and conducted full-scale tests of chlorine decay in paved and unpaved ditches and swales.

I would love to see more research being conducted on the dissipation of disinfectants in receiving waters. I’ve tried to talk with the Water Research Foundation about this topic, but all eyes are on “forever chemicals” now.

In addition, most routine maintenance-related flows for flushing and flow tests last only for a short period of time which would minimize the environmental impact of the disinfectant. The standard should also distinguish between controlled discharges from flushing and flow tests, versus uncontrolled discharges from pipe breaks or firefighting where it is generally not feasible to dechlorinate.

Avoiding chemical dechlorination can eliminate major labor, equipment, and chemical costs. However, 655 is coming up for renewal and if no one (other than me) raises these issues, it will be approved for another five years. If you want to talk about it, you can contact me at [email protected]. I’d love to hear other people’s thoughts on the subject and this blog. If you want to join the C655 Standard Committee, you can contact Amanda Dail at [email protected].

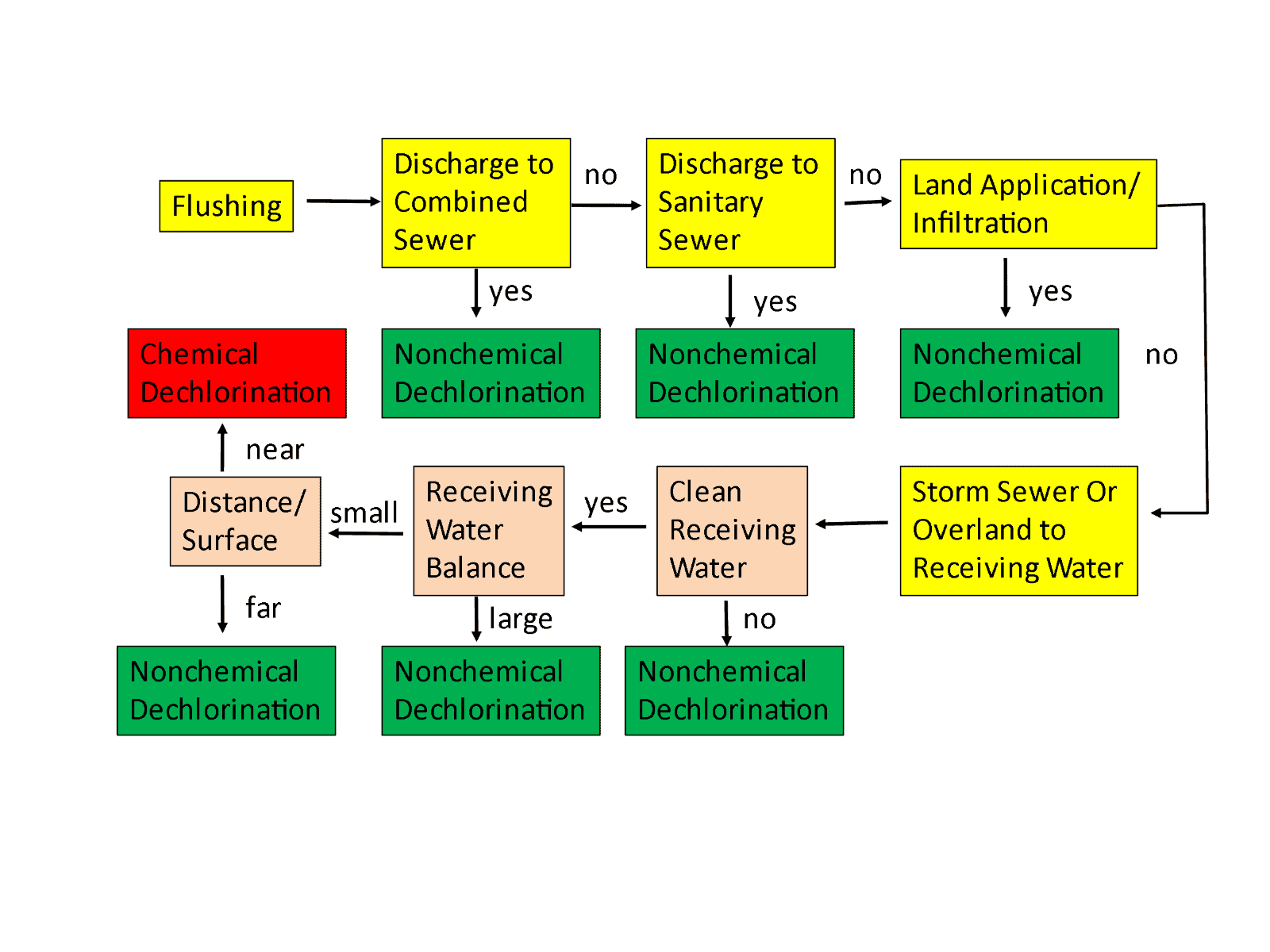

In my earlier papers, I developed a protocol for deciding if chemical dechlorination is necessary. It isn’t all that different from C655 except for the three orange boxes which account for dilution, time of travel, and reaction. If the chlorinated water flow is small compared to the receiving stream, the receiving stream has species that react rapidly with disinfectants, or there is a substantial distance/time between the discharge point and receiving water, then chemical disinfection may not be required.

Even though C655 attempts to justify the ability to adequately dechlorinate prior to the “loss of control,” chemical dechlorination has many variables and can be difficult to control at any flow; furthermore, an excess can lead to stripping oxygen out of the receiving stream. There is no requirement in C655 to ensure that a harmful dose of dechlorination chemicals was not used.

There are actually three separate use cases that the standard may be able to address.

- Getting rid of a high concentration of chlorinated water after disinfecting a new pipe. The standard does a good job of helping the engineer decide if land application or sewer discharge can be used to forego chemical disinfection.

- Explaining what to do if you have a large release of drinking water during a fire or a major pipe break. The standard doesn’t address this because there isn’t much that can be done.

- Short-term discharges of disinfected drinking water during flow tests, flushing, or other maintenance. The standard doesn’t recognize ways that dilution and reaction can render chemical dechlorination unnecessary.

There is also the question of whether C655 should even be a standard. Standards for something like this should be written in terms of performance. For example, “chlorine and chloramine entering receiving water should not cause an increase in disinfectant concentration in the receiving water greater than 0.02 mg/L and the dechlorination should not lower the oxidation reduction potential below 0.1,” but this type of wording is more in the purview of state and province regulatory agencies, not AWWA. Standards are used primarily in contract documents for equipment and chemicals to ensure they are acceptable. Standard C655 is written more along the lines of a manual or marketing material for dechlorination chemicals.

If you enjoy lugging around dechlorination equipment and buying chemicals, then you don’t need to get concerned with C655. But if it is an unnecessary use of resources, you should be concerned.

References:

Walski, T., Helsel, E., Strickland, C., Whitman, B., 2013, “Chlorine Decay from Hydrant Discharges,” AWWA-Distribution System Symposium, Itasca, IL, Sept.

Walski, T., Helsel, E., Strickland, C., Whitman, B., 2015, “Decay of Disinfectant Residuals in Overland Flow,” Urban Water Journal, Vol. 12, No. 8, p. 639, 2015, DOI 10.1080/1573062X.2014.939091.

Walski, T., Whitman, B., Douglas, L., Casey, L., 2019, “When do you Need to Dechlorinate Hydrant Discharges,” AWWA Annual Conference, Denver, Col., June.

If you want to contact me (Tom), you can email [email protected].