When Tom Walski was growing up in northeast Pennsylvania, air pollution and contaminated water were evident all around. “It was a poor coal-mining area that had just about every type of environmental problem you can imagine,” he says.

Spurred to action, Walski combined his aptitude for math and computers with an interest in the environment—and he launched a career in environmental and water resources engineering. His has been a winding professional path, from the Army Corps of Engineers to stints in Austin, Texas, and Pennsylvania’s Wyoming Valley. He’s also been active in the American Water Works Association and the American Society of Civil Engineers.

All of that experience eventually brought him to Bentley Systems, the infrastructure engineering software company. “It’s been a lucky career choice,” says Walski, who serves as an industry analyst for water and wastewater solutions at Bentley. “I enjoy what I’m doing. It’s almost always fun to go to work.”

One constant he’s noticed and contributed to along the way has been the increasing digitalization of the water industry, a process that has removed a lot of the “grunt work and manual calculations” from water engineers, Walski says. “Digitalization has coursed through many areas.” (Read his full rundown of water digitization.)

“But the problems remain the same as they were a century ago: picking the right pipe size, buying the right pumps and locating tanks in the right places for a water system. It’s just that the calculations have gotten faster, more precise and more thorough.”

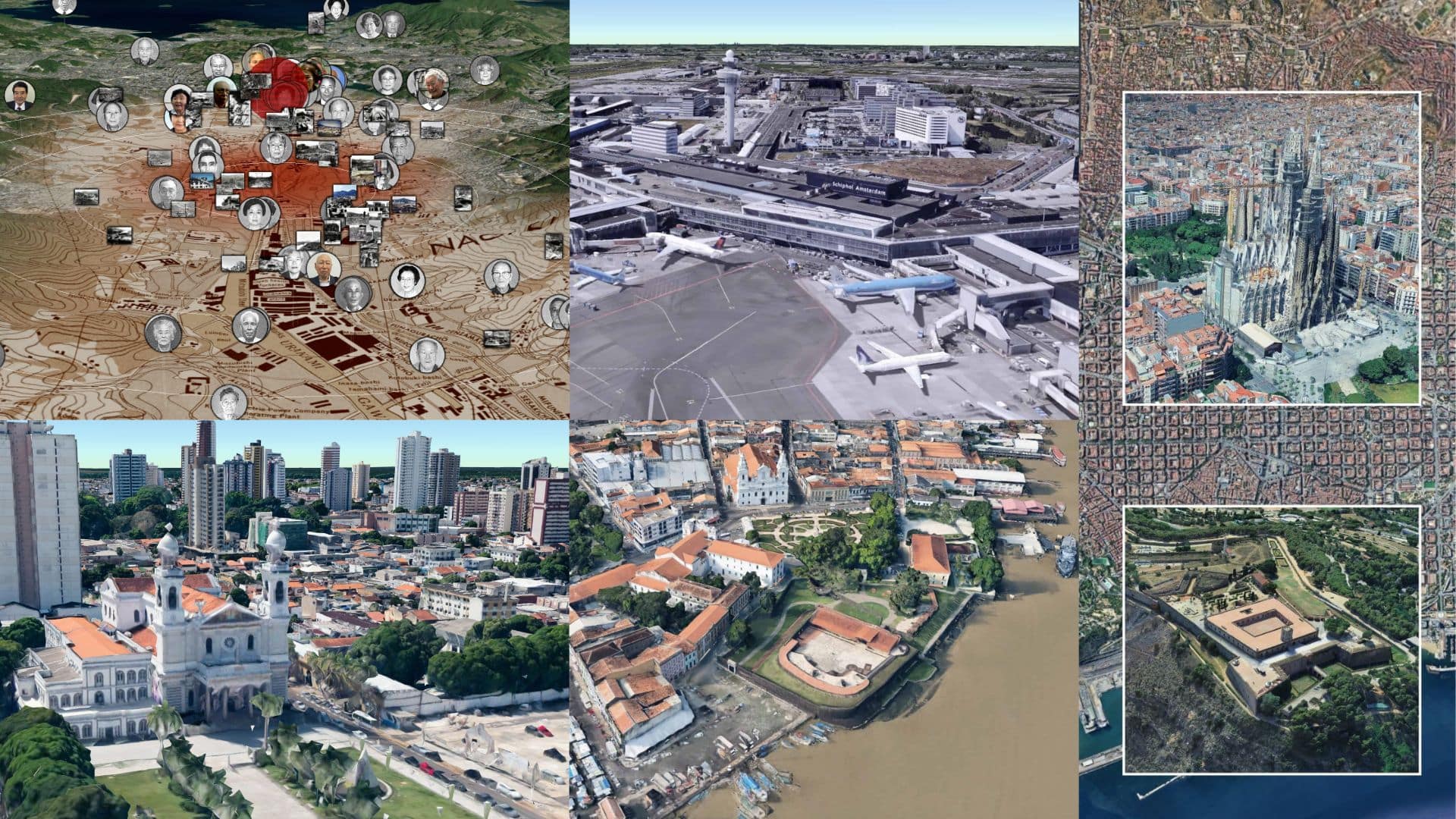

This screenshot shows an example of a water digital twin that bridges GIS data and SCADA data. In this particular example the digital twin is being used to show water outages.

This screenshot shows an example of a water digital twin that bridges GIS data and SCADA data. In this particular example the digital twin is being used to show water outages.Walski says digitalization helps hydraulic engineers look into the future. They need to know how the pipe they’re designing is going to work when it gets in the ground, but they also need to know how it will perform in five years or 25 years. How will the pipe operate on a peak day? How will it handle a fire in that part of the network? “You couldn’t do many of those kinds of calculations manually in the past,” Walski says. “Now it’s just a snap of the fingers. You can just answer so many more ‘what if’ questions and make sure that our designs are more robust and cost-effective.”

An explosive inferno

The tragic wildfires in Los Angeles have brought broad public attention to urban water systems. In early January, the raging wildfires overwhelmed the city’s water system, which was designed to fight smaller, urban fires—not the cataclysmic infernos that were engulfing entire neighborhoods. Hurricane-force winds swept through the region, making it impossible for helicopters and planes to drop fire retardant and water. “The tragic fires in LA were very unique,” Walski says. “From my perspective, LA appeared to be among the best cities prepared for an intense fire scenario. But we’ve never had to pull that much water out of a water system before. It was far beyond the reality that we’re used to living in.”

Less than 18 months earlier, similar wind-fueled wildfires in Hawaii swept through Maui, destroying the town of Lahain Under normal circumstances, Walski says, water utilities use records of past fires to ensure they meet their needed “fire flow,” which is the amount of water needed to fight a fire. “Fires of the magnitude of the LA or Maui fires in Hawaii have not occurred historically, so there is little data about needed fire flows for this size fire,” he says. “All industries and communities learn from history. There is little history for this type and size of fire.”

Climate Change as a Water Crisis

Nature has been adding examples to this lean yet devastating history in recent years. The fires in Los Angeles, for example, were a consequence of a hotter, drier atmosphere brought by climate change, according to a group of scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles. They concluded that the fires were so intense because of 2024’s higher summer and fall temperatures, which made the vegetation where the fires started 25% drier than usual. Plus, there was more of that dry fuel ready to burn: The previous winter had been unusually wet, which caused more vegetation to grow in the spring.

Explosive wildfires. Flooding. Drought. Water shortages. Extreme weather events are occurring more often and with greater intensity, a trend that scientists link to climate change. And water is tightly intertwined with climate change: The United Nations has called climate change “primarily a water crisis.”

Adding to the strain on water resources is increasing global demand for water, which is projected to grow by up to 25% by 2050. There’s also urbanization. Today, just over half the world lives in cities, and urban populations are set to double by 2050, the World Bank estimates. As more and more people live in cities, that puts an additional strain on creaking infrastructure. One example is Mexico City, which is among the world’s largest cities. The city is facing a water crisis, and it’s already losing a staggering 35% of its water because of leaky pipes, according to a recent New York Times report.

Smart solutions to managing our water resources are needed worldwide.

How Digital Twins Can Help

A digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical piece of infrastructure, such as a road, a water or sewer system, or even a whole chunk of London. Digital twins take hydraulic analysis to another level by integrating hydraulic system design with construction, operation and maintenance. The digital models also feed insights back into planning and design as the system evolves.

Walski describes digital twins as the latest step along the path of digitalization in the water industry. Municipal leaders and others around the world are increasingly using digital twins to design, build and operate their water systems and to manage their water resources.

Capture of operational zones from the hydraulic model and digital twin of the 24-hour supply scheme in Ayodhya, India. Courtesy of Geoinfo Services.

Capture of operational zones from the hydraulic model and digital twin of the 24-hour supply scheme in Ayodhya, India. Courtesy of Geoinfo Services.Recent examples include India’s holy city of Ayodhya, where an aging water network struggled to keep its residents—and millions of visiting pilgrims—supplied with water. A digital twin of the network allowed operators to pinpoint where best to make repairs, deploy new pumps, and monitor and guide maintenance.

Digital twins are also helping in Greece, where public water systems were losing about a quarter of the water they produced every year, according to a 2017 report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The city of Kozani used a digital twin of its water system to identify leaks, make repairs and lower bills for residents.

The digital evolution in the water industry hasn’t happened overnight, and progress has taken longer than Walski once predicted. But he says a certain reluctance to embrace change is understandable in the water industry, where failure—or one bad decision—can carry heavy costs.

“In an industry like water, [the] consequences are pretty severe if you don’t do a good job,” he says. “People don’t want to take risks unless they’re really sure that it’s going to make everything better.”

Read more of Tom’s blogs here, and you can contact him at [email protected].

Want to learn more from our resident water and wastewater expert? Join the Dr. Tom Walski Newsletter today!