You get a pressure reading of 62 psi. What does that mean? Is it:

- 62.0000 psi

- 62 +/- 5 psi

- Somewhere around 62 psi

Who really cares?

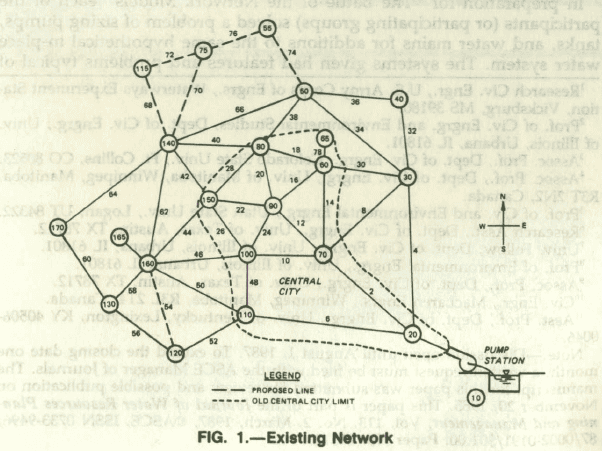

A lot depends on why you are collecting that data. Is it just for a quick check; is it a value displayed in the SCADA system; is it part of a pump test; is it being used in a hydrant flow test; is it being used to trigger alarms; is it being used to calibrate a hydraulic model?

The expectation of accuracy depends on the use.

You may want to ensure that the pressure is somewhere between 40 and 80 psi. So, readings of 47, 65, or 71 are more or less equal. In most cases, however, you are expecting your readings to be somewhere around +/- 1 psi. For use cases, such as pressure-based controls, anomaly detection, alarms, pressure-based demands, and, for me, model calibration, I’m expecting at least that level of accuracy.

Even a new pressure gauge may not be accurate, but accuracy also tends to decrease over time. Pressure gauge accuracy should be checked at regular intervals. In my experience, the typical calibration interval for most water and wastewater system gauges is never. It’s not uncommon to see gauges that have been in service for decades. In some cases, this works out fine, but you can’t be sure without calibration.

How do you achieve this assurance? The standard method is a dead weight pressure gauge tester. If your gauge tests well, you can use it with confidence. If it is out of calibration, adjustments can be made to good quality gauges. In other cases, you can develop a calibration table or curve relating a pressure reading to the actual pressure. Worst case, you can toss the bad gauge into the trash. If you leave it lying around, someone may use it. Incorrect data can be worse than no data.

Some folks will tell me that they check their gauge by comparing it with a “good gauge.” My question then is “How do you know that the ‘good gauge’ is accurate?” The response is usually a frown. To use this “good gauge” approach, it is necessary that the good gauge be calibrated recently.

Then, there is the myth of SCADA data accuracy. It’s not uncommon for a SCADA screen to display pressure along the lines of 61.4765 psi. Looking at this value, an operator may think that such a value is very accurate and precise when, in fact, the digits to the right of the decimal place are little more than random numbers. A precise digital display does not ensure accuracy.

There are standards for pressure gauge accuracy published by ASME (ASME B40.7). For most water applications an ASME Garde A gauge (industrial gauge) is sufficient as the permissible error is +/- 1% of span. There are more accurate gauges up to laboratory Grade 5A, which is +/- 0.05% of span. As the gauge accuracy increases, the cost increases significantly for a small increase in accuracy. The more accurate gauges also tend to be more delicate which is not a good trait for a gauge used in the field.

With dial type pressure gauges, the permissible error depends on where the reading falls on the span of the gauge. For a Type A gauge, for example, the error should be less than 1% in the middle 50% of the range, but it can be 2% in the lower and upper 25% of the range. This means that if you are selecting a gauge with a span of 200 psi, it should be most accurate between 50 and 150 psi.

While it’s important not to over-pressurize a gauge as that can damage the gauge, it is also important to apply gauges where they are most usable. If the range of pressures on the suction side of a pump is expected to be 5 to 15 psi, don’t use a gauge with a 200 psi span. It will only be accurate to +/- 2 psi and it will be difficult to read when the values are less than 10% of full scale.

There also is the issue of analog vs. digital gauges. All pressure data starts out as analog. However, to get to digital, it’s necessary to convert to an analog electric signal, then to a digital signal, and then transmit to a digital readout or data file. This issue is a question of who needs the data, for what purpose, and where are they located?

Pressure gauges are our friends, and we need to treat our friends well.

If you want to contact me (Tom), you can email [email protected].