Choose Area of Interest

SEARCH SOFTWARE

In the complex world of infrastructure, where sustainable design and digital innovation intersect, stories of successful project delivery often hinge not just on the software used, but on the individuals who master it. We recently spoke with Andrew Germain, an...

by Alan O’Grady

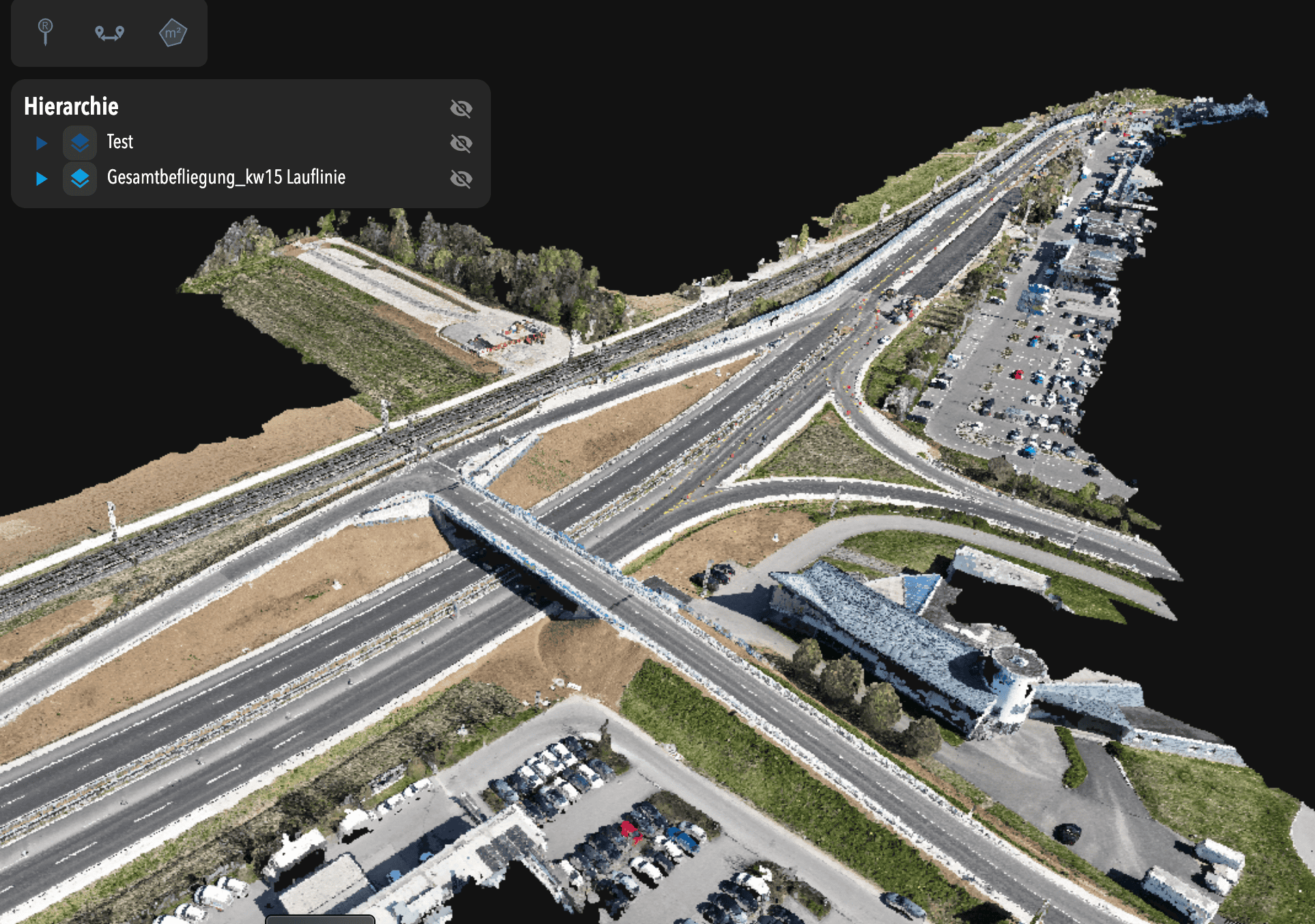

For Nicolai Nolle, CEO of Viscan GmbH, the goal was to deliver a high-accuracy digital twin for infrastructure construction—capturing and updating site conditions daily using advanced reality capture workflows. They were the digital backbone for the B29 highway expansion, a...

by Aude Camus

Seismic rehabilitation of creeping ground using a sustainable micropiled PT raft Organization: GeoStruxer Location: Jazan, Saudi Arabia Project phase: Completed and operational Estimated project cost: USD 5.4 million with a 2.1 million cost savings from optimization Bentley software: PLAXIS, RAM...

by Edita Kemzuraite

by Breda Kiely

Are You Buying Effort or Value? Rethinking Transportation Resilience. Ask 10 people in transportation what “resilience” means, and you’ll likely get ten different answers. And that’s exactly the point: resilience isn’t one thing. It includes people, data, systems, contracts, materials,...

by Amy Heffner

Imagine a workflow as dynamic as the world you’re capturing. A process where your tools don’t dictate your path but adapt to your project’s unique demands. As an engineer, surveyor, or planner, you don’t just capture data; you create the...

by Aude Camus

by Jenna Carpentier

Europe’s complex energy ecosystem infrastructure: Why the grid needs modernization now Europe’s power grid is the largest interconnected grid in the world—and it’s under pressure. Climate risks, outdated infrastructure, cyberattacks, and growing demand for renewable energy are changing the energy...

by Martha Murillo

When most people look at transmission and distribution lines, they see a series of tall towers or poles with wires strung between them. But engineers? They see art. There’s beauty in the symmetry of structures and the geometric alignment of...

by Eleanore Nguyen-Locke