I recently joined a room full of energetic infrastructure professionals for the release of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Report Card for U.S. infrastructure. Released every four years, the report gives an overall grade for U.S. infrastructure, as well as a grade and comprehensive assessment across 18 major infrastructure categories.

The good news is that U.S. infrastructure received its highest ever overall grade: C. The 2025 grades range from a B in ports to Ds in stormwater and transit. This is an increase from the 2021 Report Card’s overall grade of C-, and 2017’s D+.

This year’s increase was largely attributed to the federal government’s bipartisan efforts to pass the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which provided $1.2 trillion in funding for infrastructure. This investment catalyzed technological innovation, private finance, and ambition writ large across the sector, giving U.S. infrastructure some much-needed TLC after years of stagnation and neglect.

The energy in the room was palpable. The engineers, policymakers, financiers, insurers, owner-operators, consultants, and technology providers all shared a sense of optimism about the momentum in the industry. However, much work remains to be done. On the grading scale, a C is described as “Mediocre, Requires Attention.” Across all 18 categories, nine received a D, described as “Poor or At Risk.” In an environment where bipartisan agreement is fleeting, the fact that everyone agrees on the need to improve U.S. infrastructure is something we can and must harness.

It got me thinking, is a C really the best we can aspire to for a country that built a 46,876-mile-long interstate highway network, constructed the Hoover Dam, and sent people to the moon? How does U.S. infrastructure compare to our peers? And most importantly, how can we leverage this momentum to improve the standard of infrastructure for all Americans?

Overstretched at home. outpaced abroad

The U.S.’s bold infrastructure investment in the mid-20th century built much of the infrastructure that we rely on today. Leadership at the time created the interstate highway system, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Public Works Administration, which led to roads, rail, airports, water systems, and other infrastructure to be constructed, expanded, and improved to support the growing population and economy.

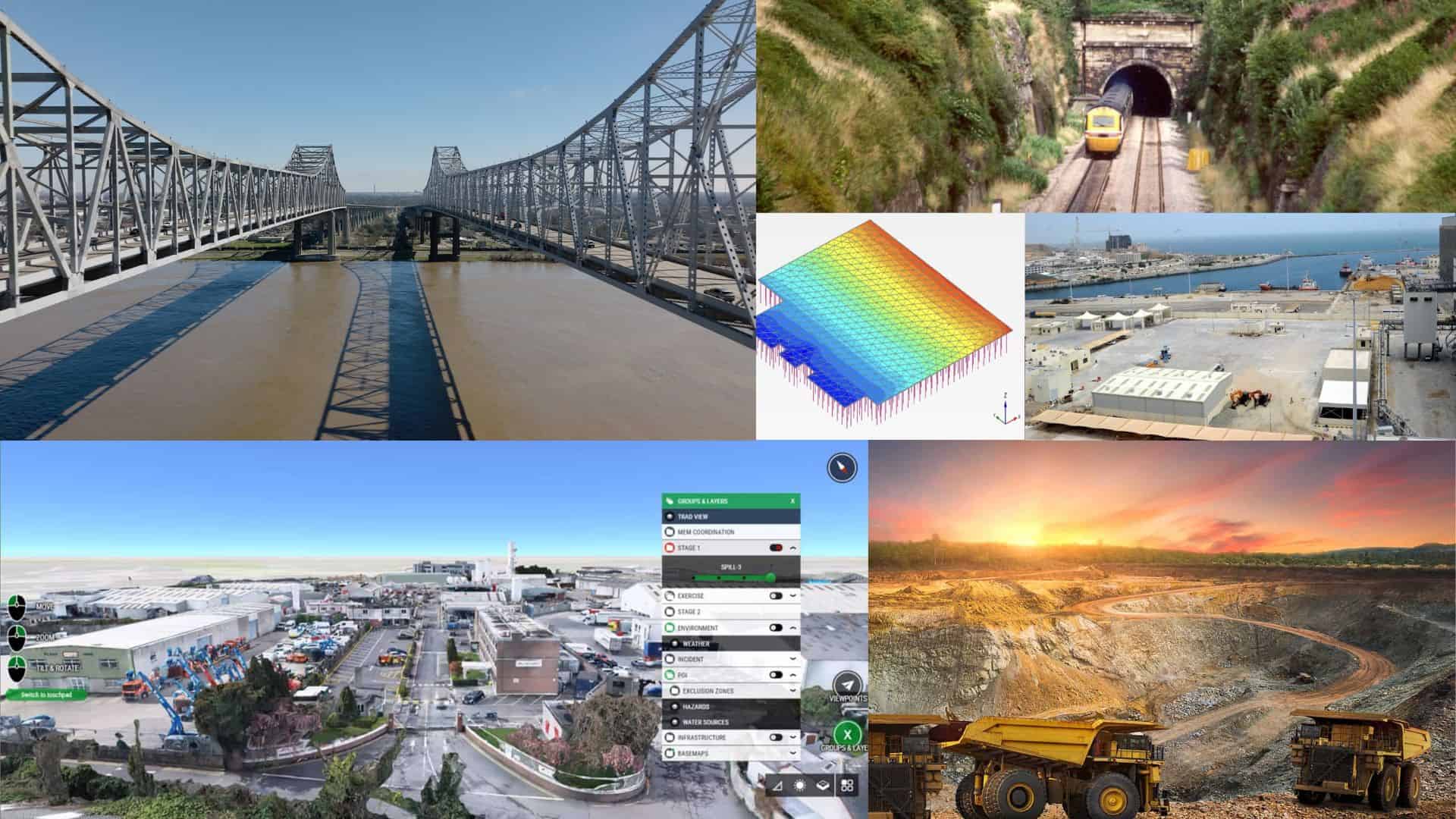

The U.S. population has almost doubled since the 1960s, when much of the country’s major infrastructure systems were constructed. Take roads for example: ASCE estimates that 39% of major roads are in poor condition. (The state of my car’s transmission and suspension can attest to that!) Asset planning, operations, and maintenance budgets and new construction have not kept pace with economic and population growth. This has left much of the infrastructure that we rely on today at the end of its lifespan and dangerously overstretched.

From C to A: strategies for U.S. infrastructure excellence

The ASCE’s C grade is not a verdict. It’s an inflection point. To move from mediocre to world-leading, we must tackle the core constraints holding U.S. infrastructure back, including inconsistent funding, fragmented planning, outdated delivery models, and a reluctance to scale what works.

The IIJA is set to expire in 2026. Even if a replacement bill were to match IIJA funding, the ASCE projects an enormous $3.7 trillion funding gap projected over the next decade. That’s larger than the entire economic output of the United Kingdom.

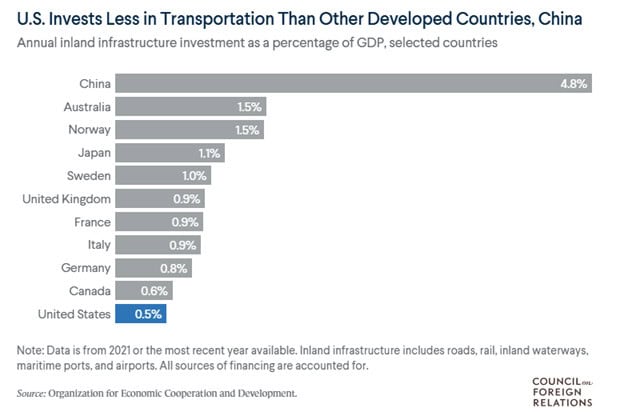

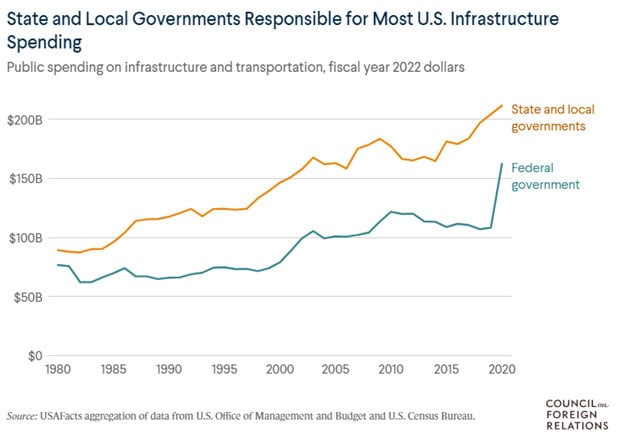

While IIJA marked a historic step—representing the largest federal investment in infrastructure ever passed in a single bill—it should be seen as a catch-up payment after decades of underinvestment. As the chart below shows, the lion’s share of infrastructure funding comes from state and local governments. That means closing the gap will require sustained and increased funding at all levels, including innovative mechanisms like public-private partnerships, user-pays models, and performance-based financing that rewards outcomes, not just inputs.

Technology is another critical component. Tools like digital twins, real-time sensors, and AI-driven maintenance planning are already being used to reduce costs, shorten timelines, and improve environmental outcomes. These innovations aren’t futuristic. They’re proven. What’s needed now is scaling them across sectors, not just in flagship projects.

To do so, we must also address the infrastructure skills gap, modernize permitting processes, and streamline regulatory frameworks to unlock innovation at speed. Resilience must be non-negotiable. From adapting to climate change to hardening our energy grids and water systems, we must build not just for today but for the shocks and stresses of tomorrow. The data proves that we save lives and money by investing for resilience rather than having to clean up and rebuild following disasters.

The U.S. has the resources, ingenuity, and momentum to lead the world in infrastructure again. But it will take more than optimism. It will require action that is coordinated, innovative, and sustained.

Let’s not just accept a C as the best we can do—we need to harness our planning, building, and innovation for an A.

Rory Linehan serves as director for infrastructure policy advancement (IPA) at Bentley Systems. You can reach out to him at [email protected]. Visit the IPA website.