New Orleans is home to awe-inspiring music, food and street parties. But let’s not forget equally awe-inspiring infrastructure, which keeps the Big Easy dry. That was evident in early March when New Orleans entered “Deep Gras,” the boisterous coda to months of revelry culminating in Fat Tuesday, the end of the Mardi Gras season. Sitting on land near and below sea level and surrounded by water, the party could go on thanks to a ring of levees, floodgates, pump stations, spillways and other infrastructure.

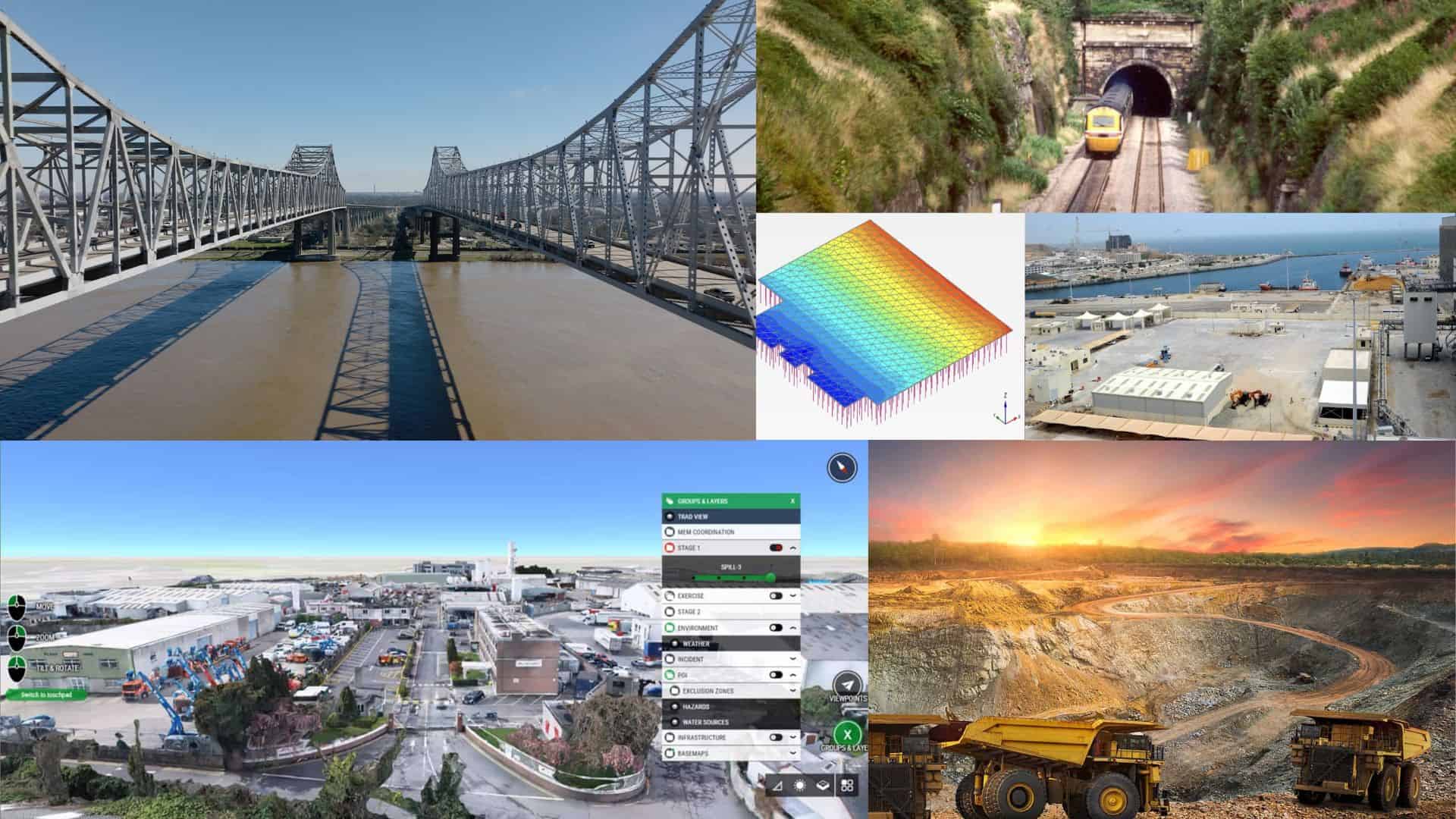

Many of these structures were built or reinforced after the catastrophic flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, including the city’s new “Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System,” a 130-mile-long flood wall completed in 2022. Dubbed as the “great wall of New Orleans,” the concrete and steel wall is the largest project in U.S. Army Corps history. “We have the most robust and complex infrastructure here in Louisiana, especially around the city of New Orleans,” says Joey Cocco, president and CEO of the Louisiana engineering firm Forte & Tablada. “The city started in the highest point here, the French Quarter, and it grew out from there. The levees and other infrastructure form a system that protects 635,000 people and assets, and industry worth billions, including tourism.”

Bentley’s Chief Storyteller Tomas Kellner (left) and Joey Coco, CEO of the engineering firm Forte & Tablada and founder of Digital-Twin walk along the spillway on the way to Baton Rouge.

Bentley’s Chief Storyteller Tomas Kellner (left) and Joey Coco, CEO of the engineering firm Forte & Tablada and founder of Digital-Twin walk along the spillway on the way to Baton Rouge.This state-of-the-art defense mechanism is just the beginning, says Coco, who recently founded the consultancy and training firm Digi-Twin Global. He believes that New Orleans and other cities must gather data, learn from it and digitize their infrastructure to stay ahead of the changing climate and the needs of their residents and economy. “One of the issues with Hurricane Katrina was a lack of understanding of how all these intricate parts came together,” Coco says. “We had data but didn’t have the ability to understand the entire system as a whole living, breathing system.

Coco says infrastructure digital twins will incorporate artificial intelligence (AI); change how we design, build and operate our infrastructure; and transform the entire sector. “The future of digital twins is going to be what you can do with the data,” he says. “From machine learning to AI, all the potential that’s going to come out of that. Once you have all the data compiled into one space, it’s just going to be unbelievable. It’s going to make the twin informative and intelligent.”

Rocket science

Obviously, New Orleans isn’t just parties. One of the organizations protected by the “great wall” is NASA. Its campus in nearby Michoud made parts of Moon-bound Saturn V rockets and Space Shuttle components, and is now building Artemis, a ship designed to fly people to Mars. Incidentally, it was NASA engineer working at Michoud named John Vickers who, together with engineer Michael Grieves, coined and popularized the term “digital twin”—a virtual model of a real thing, even a system as large as a city. “Our idea for the digital twin was just to solve problems that we had in manufacturing and product-lifecycle development,” Vickers says. “But it’s just grown so much more since then.” He believes digital twins can help us combine powerful trends including massive amounts of diverse data, AI, cybersecurity and virtual reality. “There’s got to be an approach that assimilates all of that information into some coherent information that we can pass along—and it’s the digital twin, Vickers says.

Pump It Up—And Out

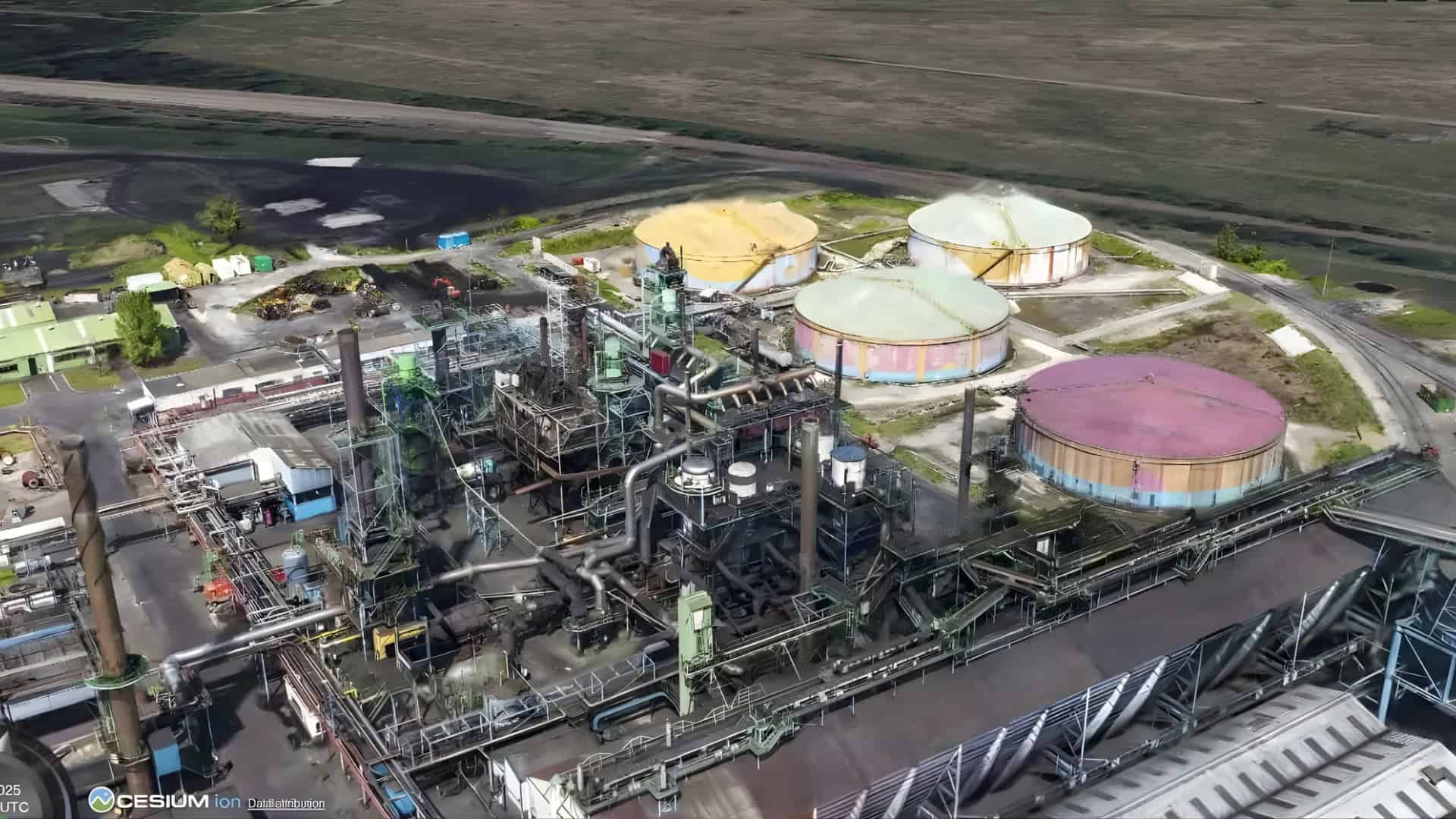

Coco couldn’t agree more. In fact, his firm already helped the Louisiana Flood Protection Authority create a digital twin of the 17th Canal Pump Station, a critical component of the big wall. The pump station, one of the largest in the world, takes water from a critical canal that drains New Orleans and parts of Jefferson Parish and dumps it into Lake Pontchartrain. The station’s pumps are so powerful that they can drain an Olympic-size swimming pool in just a few seconds. The firm gathered detailed engineering information by using an array of advanced data collections tools, such as LiDAR, along with photogrammetry and drones, even flying them inside the pump station’s dark underground chambers. Coco’s team fed the data into a suite of software programs developed by Bentley Systems, the infrastructure engineering software company and leader in digital twin technology. Using Bentley iTwin platform for infrastructure digital twins, and programs like Context Capture and Open Cities Planner, Coco’s engineers created a virtual replica of the massive facility.

“This is the next frontier,” Coco says. “All this infrastructure is analog, and the opportunities to convert it to digital are unbelievable. We’re ready to make that happen. We’re ready to drive the industry forward.” Coco says this digital transformation needs to happen. “There’s going to be a tremendous benefit to society by having all this information compiled in one space where every stakeholder has the possibility to interact with the digital twin,” he says.

We can all be part of this ecosystem. Engineers, business executives, government officials and even the public each derive unique value from the model, Coco says. “Owners can get engineering-grade information and use it to make decisions and operate infrastructure. Engineers can move straight into design, executives can look at data specific to a business case, and the public can better understand issues inherent in projects and the impact of proposed solutions.”

Age Doesn’t Matter

The 17th Street Canal Pump Station is a critical part of New Orleans’ flood control system, helping to prevent flooding during storm events.

The 17th Street Canal Pump Station is a critical part of New Orleans’ flood control system, helping to prevent flooding during storm events.The 17th Street Canal Pump Station is just one piece of river infrastructure that could be digitized in the future, Coco notes. During the waning days of Deep Gras, he took visitors on a tour of Mississippi levees, bridges and spillways that are potential targets for digital twins. One stop was the imposing Bonnet Carre spillway. Built after the devastating floods of 1927, the spillway acts as a 1.3-mile-long safety valve that can divert water from the mighty Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain, some 30 miles upstream from New Orleans. It opens when the level of the Mississippi reaches 17 feet and the river, which drains nearly half of the continental U.S., rushes 1.2 million cubic feet of muddy water per second toward The Big Easy. The spillway, a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, relieves pressure on levees downstream and protects the city from flooding. A digital twin of this critical, century-old piece of infrastructure could help the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintain it, operate it, and make faster decisions.

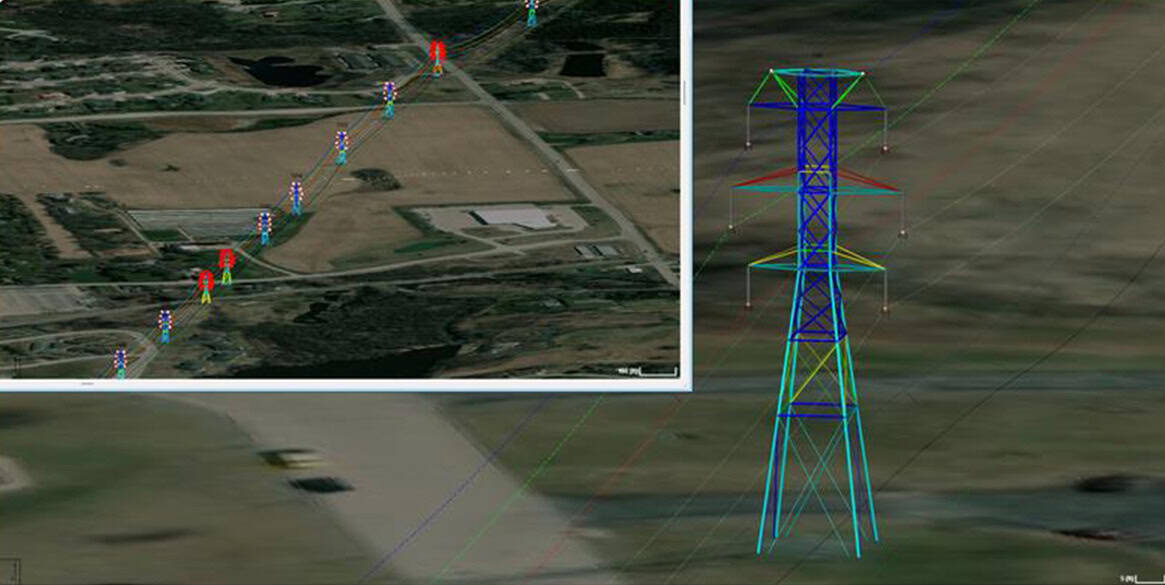

“Digital twins, with a combination of survey data, geospatial information and even 3D tiles and AI give you this canvas where you can essentially digitally replicate existing infrastructure. Whether it’s 90 years old or 150 years old, it doesn’t really matter,” says Dustin Parkman, vice president of Bentley’s Industry Solutions group. The digital twin allows engineers to quickly pull up information that might have been hard to find. “If I want to go find a detail about one of those areas where you’re opening it up to release the water, I can just select that and then find the details,” Parkman says.

Digitalizing The Mississippi River

Parkman and Coco stopped at the spillway on the way to Baton Rouge, where Coco’s other company—the digital twin consultancy Digi-Twin Global—was holding a two-day digital twin symposium at Louisiana State University. LSU is perhaps the first U.S. university offering a Master of Science degree in digital twins, and the school is keen on ensuring that its students graduate with the latest skills. Vickers, the NASA engineer, was one of the speakers at the symposium, as was Malay Ghose Hajra, chief engineer at the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority. “The kids, they are the future of this, right?” says Parkman, whose company sponsored the symposium. “They are the ones who are going to be the next leaders of our industry.”

Dustin Parkman, VP of Industry Solutions (left) and Kellner discuss water resiliency.

Dustin Parkman, VP of Industry Solutions (left) and Kellner discuss water resiliency.LSU’s tools include a unique model of the last 178 miles of the lower Mississippi. Located at the school’s Center for River Studies, the model is the size of two basketball courts and is so precise that Mississippi boat captains come here to study it. The students use it to model sediment flows in the river and simulate flooding conditions. They gather data and feed it to a computer model to collect insights. On a recent visit, students were sending water through their model of the Bonnet Carre spillway.

Hayden Franklin, who is studying coastal engineering, says he grew up “on the river” and was always fascinated by it. He’s now earning his graduate degree and working on a research project that is helping the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers get smarter about dredging. Specifically, he and his classmates are studying the impact on sediment flows of the Mid Barataria Sediment Diversion in the Mississippi Delta, one of the most expansive coastal projects in the country’s history. They gather data from their model and compare it with information coming from the “real” river. “I think we’re one piece in the big puzzle,” Franklin says. “There’s a whole lot of different factors. But I do think the work that we do here can help contribute to the grand scheme of things.”

Coco says models like this one, along with the data gathered by Franklin and other students, also can be used to feed digital twins. “This is an analog model with a lot of digital to it,” Coco says. “The goal is to try to get all of this information and couple it with the actual river to create a digital twin of the entire Mississippi River system, analyze it and understand it.”

With so many lives and livelihoods at stake in Cajun Country—and so much history and culture—it’s a worthy goal.