I’ve lived in Asheville, North Carolina, for nearly 20 years, and each season brings its own charm. Spring is a riot of flowers, summer offers a cool escape from the South’s humidity, and winter often blankets the area with storybook snowfalls.

But fall in the Blue Ridge Mountains is truly special. Come September, Asheville becomes a magnet for leaf-peepers, hikers, and craft beer fans, all drawn by the crisp air and vibrant foliage.

This year is different. Hurricane Helene ripped through the region just over a month ago with catastrophic rain and wind, drawing FEMA trailers and National Guard convoys instead of tourists.

I write often in these pages about the future of infrastructure. But Helene taught me what it means to live without it. I learned first-hand why we need resilient roads, bridges, water networks, power grids and other critical systems to handle what Mother Nature throws at us.

“It smells like Christmas”

Storms of Helene’s magnitude rarely threaten cities like Asheville, which sits more than 2,000 feet above sea level and 300 miles from the ocean. Unlike hurricane-prone beach towns in Florida or along the Gulf Coast, Asheville is nestled in a densely forested area with thousands of towering, mature trees. But the week Helene hit the U.S., the weather delivered us a one-two punch.

A storm system passed through Asheville the day before Helene’s arrival, drenching the area with 6 inches of rain. Then on the morning of Sept. 27, my 14-year-old daughter, Rose, and I woke up in darkness to howling 45-mph winds and torrential rains. We heard loud cracks as transformers blew, and we watched 100-foot pine trees fall like giant dominoes, taking down utility lines and blocking streets in our neighborhood.

“It smells like Christmas,” Rose said.

The lucky ones

The author and his daughter, Rose, during a visit to Charlotte, North Carolina, to catch up on work in a space with power and internet.

The author and his daughter, Rose, during a visit to Charlotte, North Carolina, to catch up on work in a space with power and internet.Helene stalled over western North Carolina, dumping four to six months’ worth of rain in about 24 hours. Unlike in hurricane-prone coastal towns, heavy rains cannot drain into an ocean in towns like Asheville. Here, mountain ridges that drop into steep valleys cascaded billions of gallons of raging, chocolate-brown water into creeks and streams, ravaging everything in their way.

The rain set off mudslides, which engulfed highways, sent soil and rock into breached reservoirs, isolated rural communities and made it difficult for first responders to save lives and bring aid. In the initial days after the storm, there were no direct routes in or out of Asheville. With impassable sections of major highways like Interstate, supplies for the city had to be helicoptered in.

The hours and days that followed are, in my memory, simultaneously crystal-clear and murky as the relentless flood waters that burst the banks of the Swannanoa and French Broad rivers that flow through town. The water washed away roads, bridges, buildings and economic livelihoods.

We are among the lucky ones. Helene claimed at least 100 lives in North Carolina, and 2,000 people are still missing. Businesses and jobs have been lost, at least temporarily. I used to visit the River Arts District outpost of North Carolina’s famous Summit Coffee three times a week. It’s now gone. Governor Roy Cooper estimates the statewide financial impact at more than $53 billion.

A system of systems

I’ve learned a lot about the importance of resilient infrastructure by writing for Bentley Systems, but my first-hand experience in the aftermath of Helene has taught me far more than any interview or assignment ever could. These last two months have served as an eye-opening case study on the critical systems many of us unknowingly take for granted.

My Helene scorecard: Three days without mobile service, 20 days without electricity, 22 days without non-potable water, 26 days without internet. But that’s just a high-level snapshot. Life here after the storm quickly revealed just how interconnected our infrastructure truly is, and that a city is a system of systems.

We were still in a blackout when pipelines reopened and fuel returned to local gas stations, creating miles-long lines of cars. We couldn’t access the internet without power, and businesses couldn’t process credit card payments without connectivity. That meant the few open stations pumping gas were only accepting cash, which is impossible to come by without functioning ATMs or open banks.

Without Wi-Fi or cell service, we couldn’t access news or information through our phones or computers. That meant starting our cars—which requires gasoline—to tune into local public radio for twice-daily briefings from city and county officials. We also used our cars to charge our relatively useless phones.

My car was pinned in my driveway by a fallen tree, so we borrowed a car from neighbors whose names I didn’t know until that day. We inched our way downtown where we’d gotten word there was an active Wi-Fi network outside a cluster of government buildings. We huddled over our phones alongside dozens of other disoriented residents, unsuccessfully pinging the hotspot before returning home.

The storm has widened the digital divide, especially in rural communities where broadband access is a luxury on a good day. It also strengthens the case for a smarter, more resilient power grid. I briefly left town twice in the initial weeks following the storm—to Atlanta then Charlotte—primarily to work in a space with power and connectivity.

Treading water

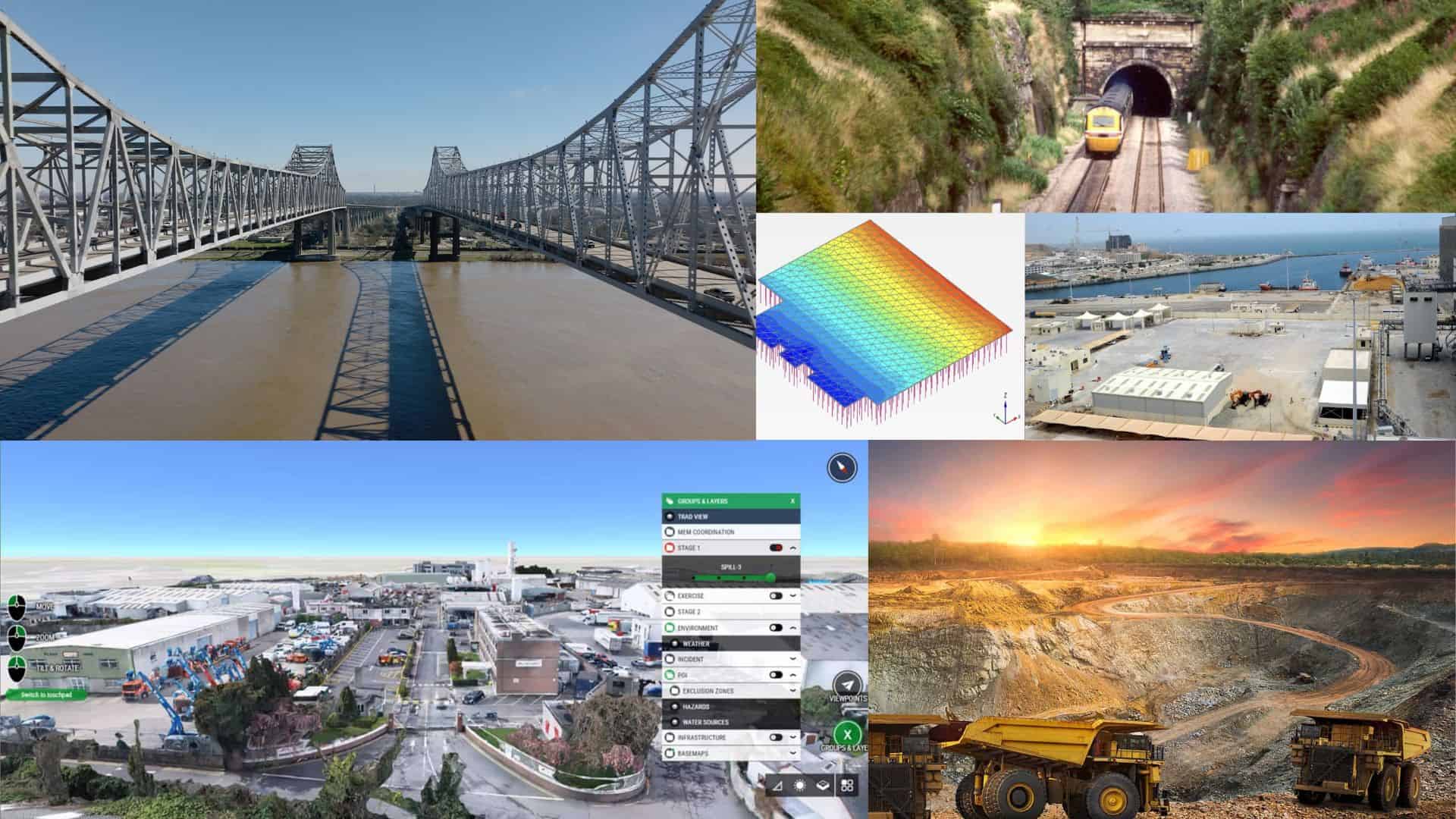

A view of Asheville after Helene.

A view of Asheville after Helene.Helene reserved its biggest blow for our water and sewer infrastructure. The storm put two of the city’s three treatment plants—which supply 70% of Asheville households—out of commission.

For weeks, that meant finding creative ways to bathe. My morning routine included carting five-gallon buckets to fetch water from a neighbor’s swimming pool so I could flush my toilets, then driving to a nearby community center to fill empty containers with potable water.

Area hospitals, inundated with emergency cases, imported tanker trucks of water to keep up with basic sanitation and hygiene needs. Restaurants only recently started to reopen, with limited schedules and menus, and temporary systems in place to safely prep and cook food. More than 40 days post-Helene, many city residents still don’t have clean drinking water, and they aren’t sure when they will.

A resilient mindset

For Rose and me, Helene has been ripe with lessons. It affirmed the power of community and the resilience of the human spirit. It brought people together to grieve, recover and rebuild. It also serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of the aging infrastructure we rely on each day—roads, bridges, power grids, cell towers, water systems—and the urgent need for reliable and resilient solutions to ensure a safer, sustainable future.