As a civil engineer with the Colorado Department of Transportation, John Kronholm keeps his ear close to ground. Or nature, to be precise.

Kronholm is the resident engineer for Eagle and Lake counties, stationed high in the Colorado mountains in the town of Eagle and spends his days ensuring that the state’s wildlife can safely cross the twists and turns of Vail Pass. The 10-mile stretch of Interstate 70 connects Vail and Copper Mountain, both popular ski resort towns, and climbs to 10,600 feet — about twice the elevation of Denver. The pass is an important access road through U.S. Forest Service lands for millions of travelers bound for ski resorts in the winter and seeking recreational bliss in the summer.

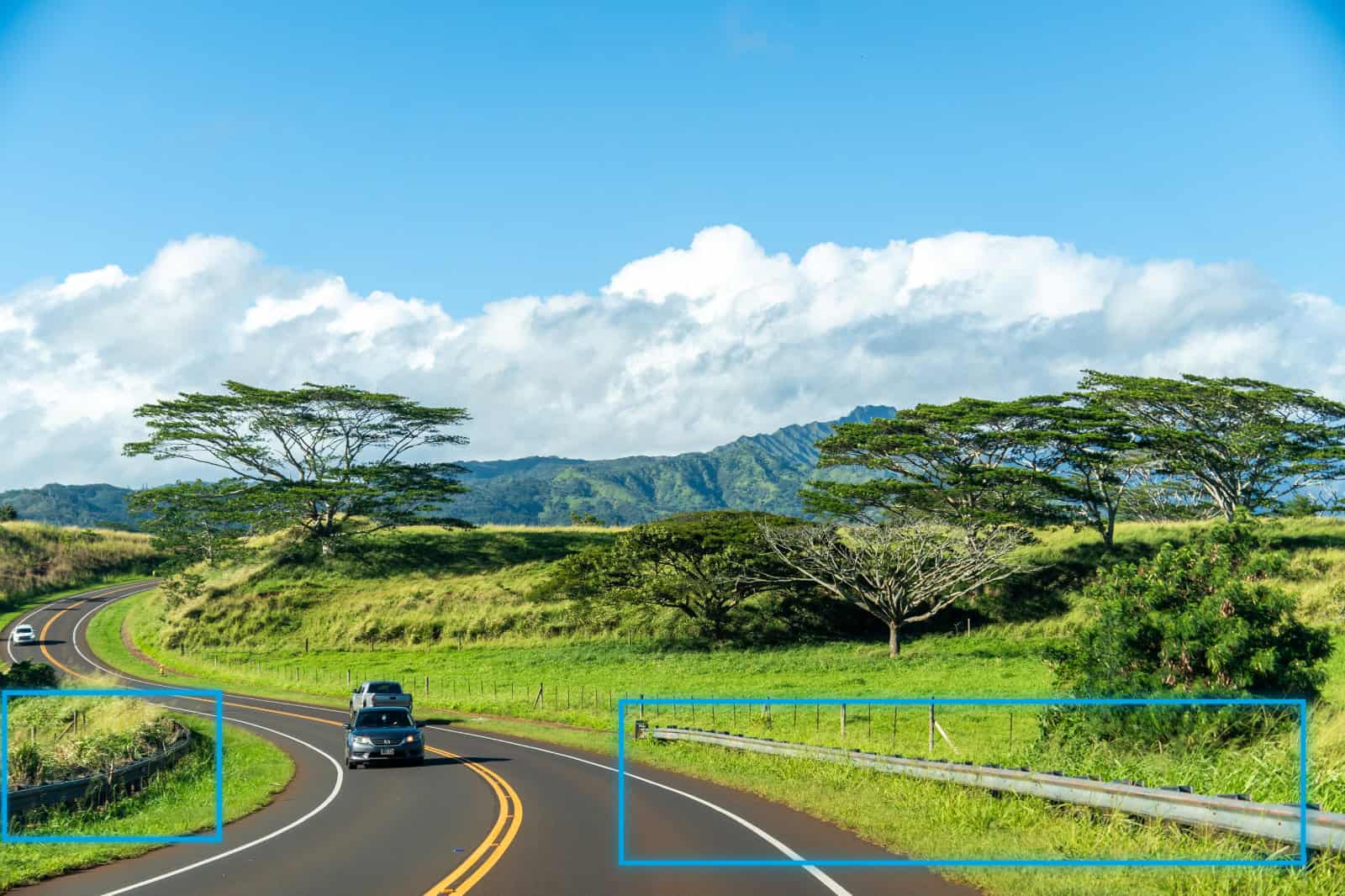

But like many roadways throughout the country, I-70 also slices through migration routes and habitat. The rugged surrounding mountains are home to mule deer, elk, Canada lynx, black bears, bobcats, snowshoe hares, foxes, coyotes and other animals. They need safe passage to cross I-70. Collisions with cars and trucks zipping by that could be devastating for both wildlife and the vehicles’ human occupants.

“There’s no doubt the highway is a barrier,” Kronholm says.

Vail Pass is now undergoing a major $325 million upgrade that includes a new lane, safer turns and safer routes for wildlife. Partial funding for the project comes from the federal Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) Grant Program. Kronholm is working with wildlife biologists, road ecologists and fellow engineers to determine how many crossings are needed at Vail Pass and where to place them.

John Kronholm, resident engineer for Eagle and Lake Counties with the Colorado Department of Transportation, readies a truck to install an electronic “WILDLIFE CROSSING” sign.

John Kronholm, resident engineer for Eagle and Lake Counties with the Colorado Department of Transportation, readies a truck to install an electronic “WILDLIFE CROSSING” sign.Kronholm and his team faced several challenges. Wildlife crossings often look like grassy bridges and tunnels, but the jagged topography on Vail Pass ruled out overpasses. Engineers were forced to find openings under the road, and they didn’t have much room to work with.

This is where Kronholm and his colleagues turned wildlife crossings into science.

The sizing of wildlife crossings can be an imprecise science, Kronholm says. For example, he realized that even small crossings could be effective after watching a video of pronghorn moving in single file across a 150-foot-wide overpass in Wyoming.

“They did not use even half the width of the overpass,” he says. “It made me wonder if we were oversizing the underpasses planned for Vail Pass.”

Kronholm gathered research from around the country looking at migration patterns, camera footage and heat maps from roadkill. Studying the data, he realized he could build a statistical model that would allow him to right-size the length, width and height for a given species.

“I came up with a statistical method to predict success rates for the use of wildlife underpasses,” he said. “I saw that crossings were often built bigger than they needed to be and that, if you could make them smaller, you could build more of them.”

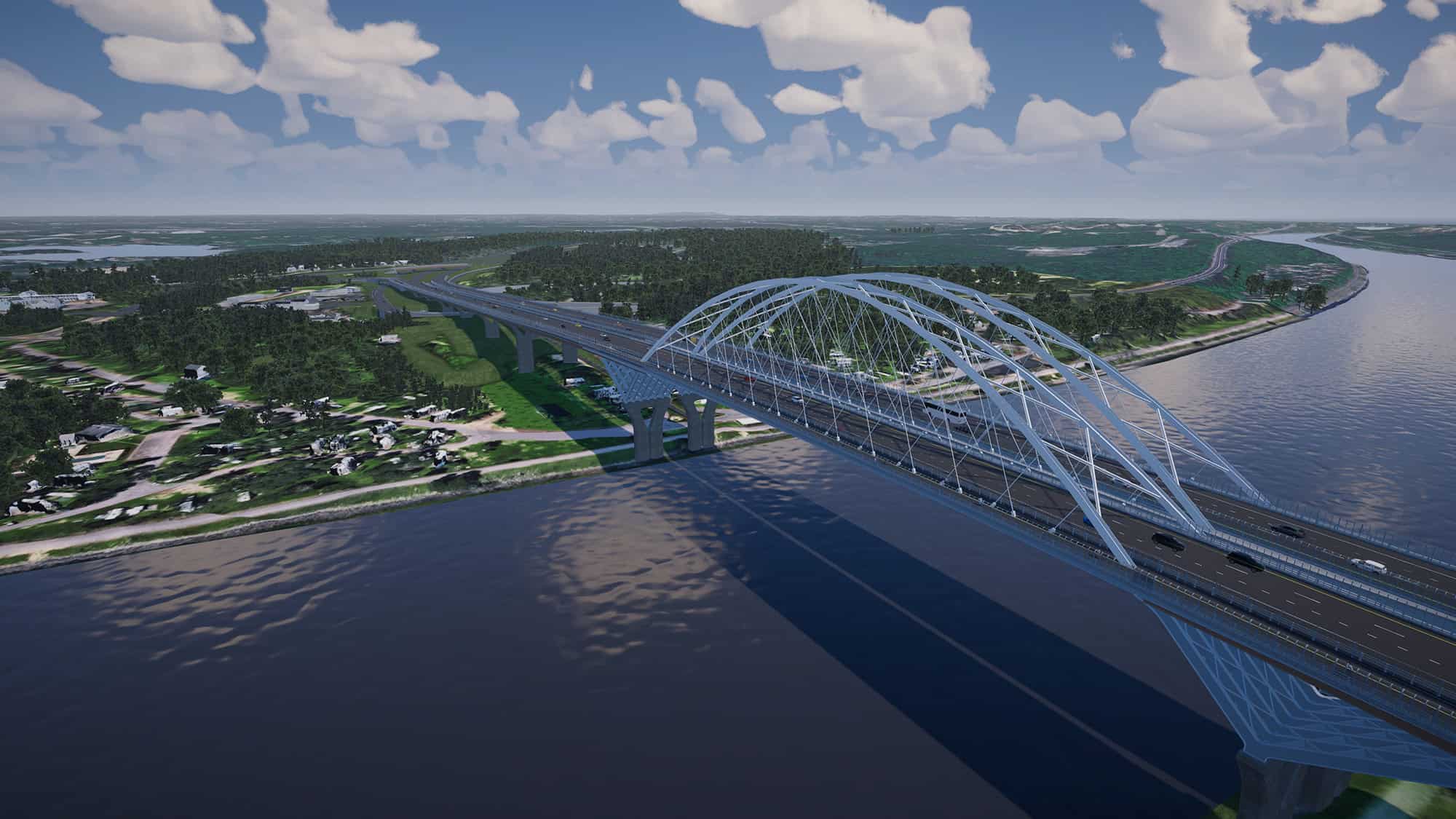

Kronholm compiled his findings in a grant application – and won. He knew that the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) was using software from Bentley Systems, an infrastructure engineering software company, to create a digital twin of the I-70 upgrade. A digital twin is a virtual representation of real-world assets. By incorporating real-time data into the digital models, engineers and other users can create a comprehensive and accurate representation of roads, bridges and other infrastructure.

But building wildlife crossings is a complex effort. It involves structural engineers, wildlife biologists, road ecologists, geotechnical engineers, drainage engineers and representatives from Colorado Parks and Wildlife. With his funding secured by the grant, Kronholm worked with CDOT and other experts to find the right spots for crossing in 3D models of Vail Pass and showed them to the project’s stakeholders. Each of the project’s two large underpasses was estimated to cost around $10.4 million. Kronholm’s insights revealed they could save $1.7 million by building six smaller crossings — four for small to medium-sized animals such as bobcats, coyote, marmot and foxes, and two larger ones for lynx, deer and elk.

The federal government estimates that over 1 million collisions occur between cars and wildlife each year nationwide. In Colorado, Kronholm says that 5% of all reported accidents involve collisions with wildlife. (That number is likely higher given the large number of roadkill — 7,338 carcasses were removed from Colorado roadways in 2022 alone — and unreported collisions.) Accidents create traffic jams, and Kronholm says that every hour I-70 is closed costs the state $1 million in lost tourism revenue. The costs incurred by travelers caught in crashes, the price of dispatching emergency services, insurance claims and other expenses push the price tag even higher.

Kronholm says safe wildlife crossings combined with wildlife fencing decrease wildlife vehicle collisions by 87%, while also maintaining or reopening vital migration paths. Once wildlife crossings are in place, it can take three to five years for animals to develop enough trust to use them regularly. But when hidden camera footage captures a herd of mule deer finally using them, it warms Kronholm’s heart. He knows that the ability to follow migration instincts is essential to the health of animal populations. It makes all the number crunching from his desk in remote Eagle, Colorado, worth it.