Otto Lynch lights up when talking about his favorite subject: power transmission lines.

“There’s nothing better than a big, beautiful lattice tower with wires or a flexible, tubular steel pole,” he says without a hint of sarcasm. “I see transmission lines as works of art.”

Otto Lynch, VP of Power Line Systems

Otto Lynch, VP of Power Line SystemsLynch is the head of Power Line Systems (PLS) based in Madison, Wisconsin. For more than three decades, PLS, which is part of Bentley Systems, the global infrastructure engineering software company, has set the industry standard for overhead power line engineering software. Although many people still view these lifelines as landscape eyesores, Lynch brings a uniquely passionate perspective on the electricity highways that feed modern life and industry. (He is so passionate, in fact, that his license plate reads “PLS.”)

It’s estimated that up to 98% of new transmission lines worldwide were designed with PLS software, which fast-tracks the production process. The software empowers a single electrical engineer to accomplish in a few months what once took a team of 50 two to three years, at a fraction of the cost. Users can design overhead transmission and distribution lines to be safely and efficiently constructed between points A and B. (See our story on PLS software more details.)

Transmission lines are becoming ever more important as they carry renewable electricity from distant wind farms to cities, powering everything from electric vehicles (EVs) to the data centers at the heart of the boom in artificial intelligence (AI). The lines are also strengthening grid resilience in the face of extreme weather and increased demand. A 2025 study commissioned by the National Electrical Manufacturers’ Association (NEMA) expects a 50% growth in U.S. electricity demand by 2050. The picture is similar in Europe and Asia.

Getting in charge

Lynch’s path to a career in engineering traces back to his childhood. His father introduced him to the joy of building metal structures with Erector Sets, which he says sparked a dream of designing “big, beautiful bridges” that he carried with him to Missouri University of Science and Technology. Lynch graduated with a civil structural engineering degree in 1988, and he had multiple job offers with top-tier engineering firms and even the Missouri State Highway Department.

But an on-campus interview with Dave Kohler from the global engineering firm Black & Veatch inspired Lynch to pivot his focus. “You might design 10 bridges in your entire career compared to 10 transmission lines in six months,” Lynch recalls Kohler telling him. “Transmission lines are built using the same components — pylons, cables, foundations — and are like giant suspension bridges that can stretch 500 miles.”

The pitch worked, and Lynch joined Black & Veatch in 1988. On his first day, his supervisor handed him a 5.25-inch floppy disk with a new lattice tower analysis program from PLS. “Nobody here knows how to use it,” his boss said. “You figure it out.”

The French connection

The software, TOWER, was originally written in Fortran, an early programming language for scientists and engineers, by Dr. Alain Peyrot, a French-born civil engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin. His son Eric, who was 14 at the time, ported it into BASIC.

“I grew up on an Apple IIe, so I wasn’t afraid of computers,” Lynch said. “I took on the challenge of learning to design and analyze transmission towers.”

When he had a few questions about the program, he dialed the number listed in the user’s manual. Peyrot answered, launching a relationship that would eventually revolutionize an industry.

Peyrot founded PLS in 1984 to provide consulting services and develop engineering software for the structural and geometric design of electric power lines. He spent years perfecting specialized algorithms for modeling transmission line structures that in the early-1990s became the PC-based transmission line design PLS-CADD (Power Line Systems Computer Aided Design and Drafting).

Lynch served as Black & Veatch’s PLS liaison.

“Alain and Eric were great software developers, but they’d never designed transmission lines,” Lynch says. “So, I taught them.”

For nearly a decade, Lynch helped shape PLS-CADD by ensuring it met practical engineering needs. The collaboration deepened when he spent two years in South Texas as a resident engineer on a 120-mile transmission line.

“I got my boots muddy, got my Carhartt’s dirty,” he remembers. “I lived and breathed transmission lines.”

True believer

Eager for his next professional challenge after a 13-year run, Lynch left Black & Veatch in 2000 on good terms. He called Peyrot asking if he could list him as a reference and got an unexpected response: “‘No, no, no!” Lynch recalls Peyrot, the man he calls a “second father,” saying in a thick French accent, “‘I want you to come work for me.'”

Hesitant, Lynch reminded Peyrot of his limited software programming knowledge or experience. “Exactly,” Peyrot replied. “I want you to do everything else.”

Lynch took a pay cut and surrendered his health insurance benefits to join the small Wisconsin company. “I believed in the product and in Dr. Peyrot’s vision for the company,” he says. “The industry was rapidly changing, with growing demand for more reliable electricity and stronger transmission lines. I knew PLS was the right solution at the right time at the right price. All planets lined up perfectly.”

For the love of the game

PLS-CADD, priced at $9,500 per copy compared to $100,000 for its lone competitor’s offering, delivered superior capabilities at a fraction of the cost. Lynch oversaw marketing, training, and business development, helping to grow the company’s customer base of more than 1,800 utilities, consultants, contractors, and manufacturers in more than 130 countries. “I’m an entrepreneur at heart who loves competition, so I was having a blast,” he says.

When Peyrot retired, Lynch and a few other employees bought out his shares. In addition to becoming an owner, he took over leadership roles with industry organizations, including the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which are responsible for setting standards for transmission line design. Lynch’s involvement helped the company stay ahead of the curve by implementing updated requirements in PLS-CADD before their release.

Seeing light in the dark

PLS’s growth accelerated through an unexpected opportunity that traces back to the mid-‘90s. An oil company using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology to map the Gulf of Mexico’s seafloor for potential drilling locations approached Black & Veatch with a problem. When they flew LiDAR-equipped helicopters over transmission lines, “those darn wires got in the way.”

Lynch seized on the opportunity and began ingesting LiDAR data into PLS-CADD software, pairing it with satellite imagery to speed assessment of existing lines. After the Northeast blackout of 2003, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) issued an alert: utilities in the U.S. and Canada couldn’t trust old drawings for lines above 100 kilovolts and needed fresh surveys. Utilities using LiDAR and PLS-CADD automatically met this requirement.

“That was a big boon for us,” Lynch says. “More than 80% of all lines in the U.S. and Canada, 100 kilovolts or greater were eventually modeled in PLS-CADD with LiDAR.”

Lynch became a crisis consultant of sorts, flying to job sites and processing helicopter-gathered data to solve critical capacity problems. “This was before USB sticks, so crews would bring a hard drive back to me in my hotel room, where I’d model the line overnight,” he recalls.

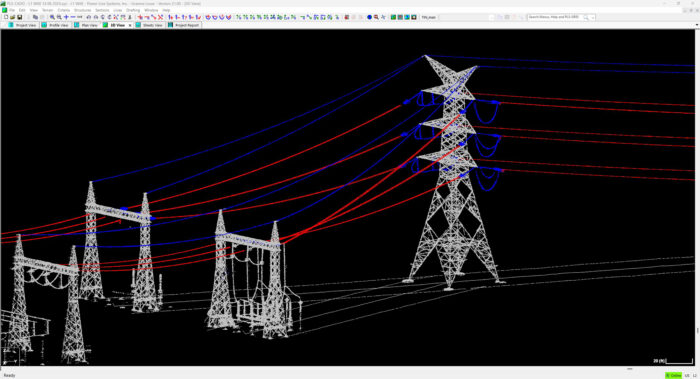

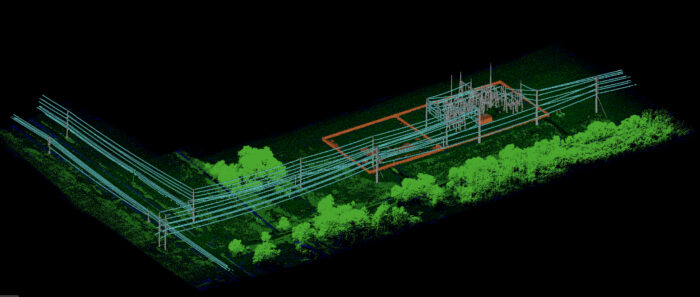

A computer-aided design (CAD) wireframe model of a power transmission tower and substation with color-coded overhead power lines generated using PLS with LiDAR.

A computer-aided design (CAD) wireframe model of a power transmission tower and substation with color-coded overhead power lines generated using PLS with LiDAR.A perfect match

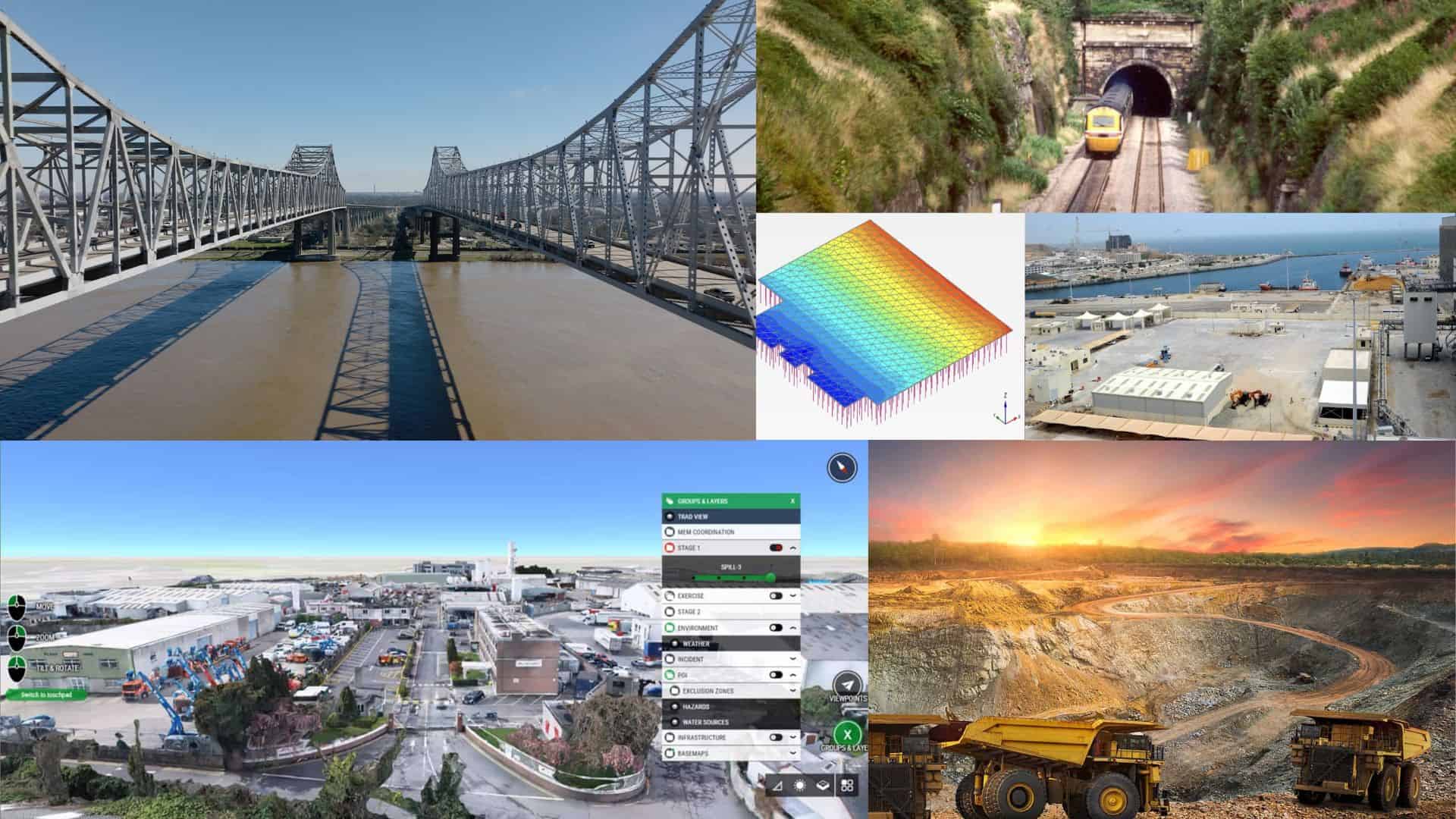

After more than two decades of steady growth, PLS was acquired by Bentley Systems in 2022. “Bentley offers applications and software across all aspects of infrastructure, and we filled a gap in the utility and power grid space with electrical transmission and distribution sets,” Lynch says. “Our job is to get electrons from where they’re made to where people want them to be, so from that standpoint, we’re a perfect match.”

The acquisition came at a critical juncture. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act had committed $65 billion for grid upgrades across the U.S., and the shift to renewable energies was sparking demand for new transmission lines. PLS is uniquely positioned to help utilities weather what Lynch calls the brewing “perfect storm” of aging infrastructure and exploding demand for reliable electricity, which is being fueled by the rise of EVs and AI data centers.

America’s energy grid rating dropped from a C to a D+ in the 2025 Infrastructure Report Card.

Many legacy components are beyond their expected lifespan — an estimated 75% are more than 60 years old — and are showing signs of wear and corrosion. Wood poles are decaying or riddled with woodpecker holes, steel poles and towers are rusted, and cross-arms are fatiguing. Unlike highly visible transportation infrastructure defects like potholes or sagging bridges, transmission lines are largely out of sight and out of mind until outages occur.

Raising the stakes

To support the boom in AI data centers alone, the U.S. needs to add 35 gigawatts of new capacity by 2030. (Lynch playfully calls the measurement “30 DeLoreans” referencing the 1.3 gigawatts needed to power the time machine in Back to the Future.)

A PLS generated 3D scan of a power substation and electrical lines.

A PLS generated 3D scan of a power substation and electrical lines.“We don’t currently have enough power to meet demand,” Lynch says. “Our grid was not designed for always-on power, which requires power line upgrades to meet modern design and engineering standards.”

The shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy adds another layer of complexity. “You don’t tear down a coal plant in Ohio and build a wind or solar farm there,” Lynch explains. “You build in South Dakota and have to get that power back to the plant they replaced. The analogy I use is we’ve taken the fuse panel in one end of our house and put it on the other end of the house, which requires significant rewiring.”

Lynch, through his leadership in ASCE and other industry organizations, is a vocal advocate for updated codes and permitting reform. In the U.S., building a transmission line crossing government land requires approval from dozens of agencies — a tedious process that creates multi-year bottlenecks that the country can no longer wait for.

“When we’d lose electricity in the ‘70s, we’d pull out a board game or play poker,” Lynch recalls. “We’d grill in the backyard, and my aunts and uncles would come over because we had a wood-burning fireplace. You could go downtown to the hardware store, where the owner used a flashlight to help you find what you needed, and you paid with cash. It wasn’t the end of the world.

“Now when we lose electricity, we can’t charge our cellphones. Kids can’t play video games, you can’t watch Netflix, and commerce shuts down. The stakes are much higher.”