On a laptop screen in a quiet lab at the University of Tokyo, the city of Hiroshima unfolds in unnerving detail. Streets, houses, rivers — all reconstructed as they stood on a bright summer morning in 1945. Then, with a few clicks, the map reveals what came after: devastation stretching in every direction.

It’s not a movie clip or a static photo. It’s a way to zoom, pan, and step through the city. This is history revealed as a living, explorable world. This is the work of Hidenori Watanave, a professor and information design specialist who has spent two decades transforming how we engage with memory. His projects include interactive archives of the people who survived the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, real-time maps of the war in Ukraine, and a full 3D model of a Japanese Navy Type Zero Reconnaissance Seaplane pulled from the sea.

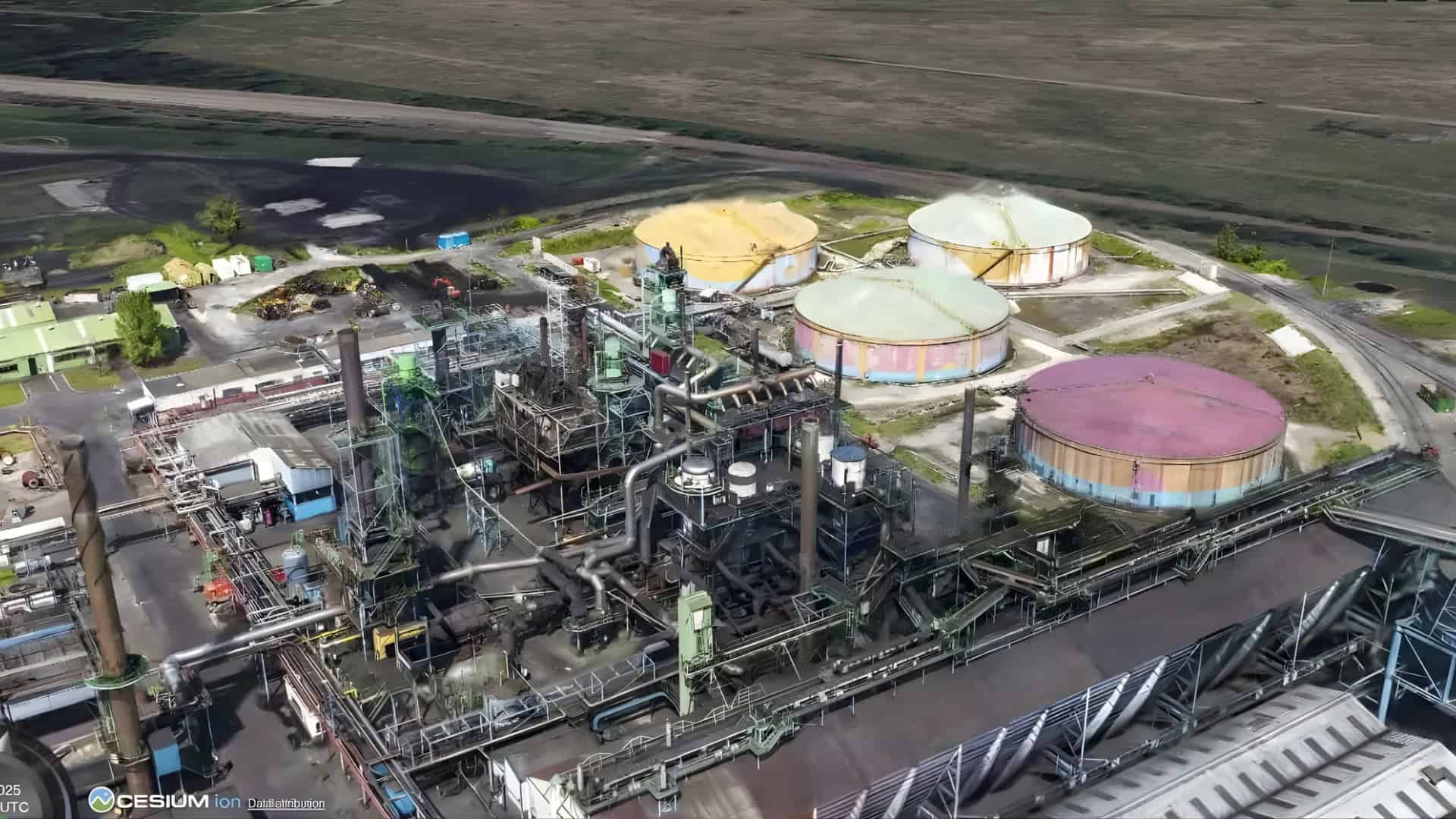

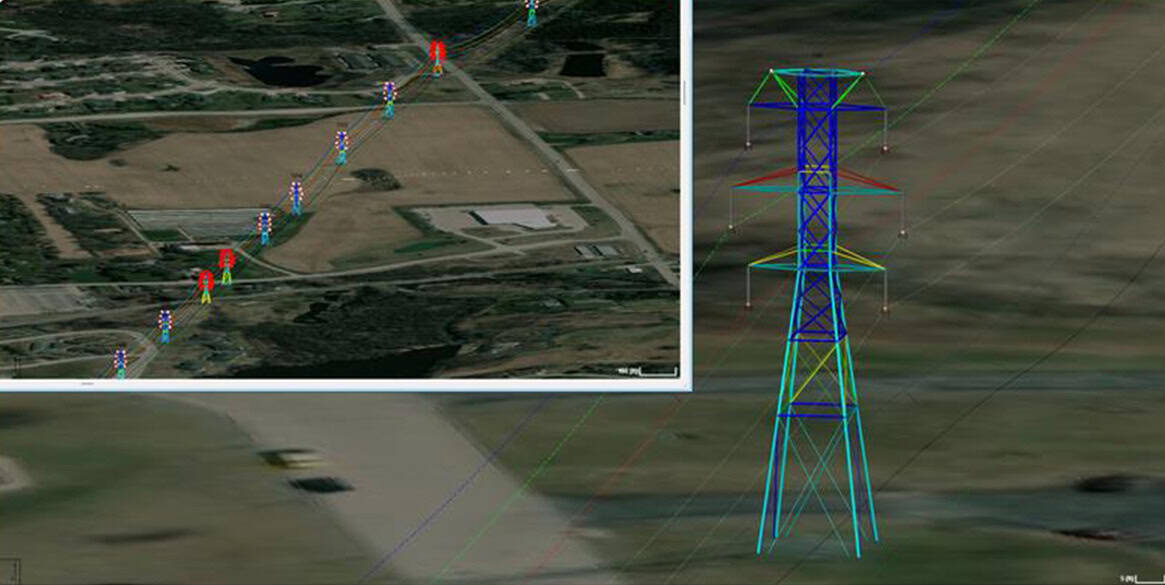

All of his projects share a single mission: to connect people across time and space, to events they might otherwise only encounter in textbooks or headlines. And increasingly, those worlds are powered by Cesium, the open-source 3D geospatial platform that can stream vast datasets into a browser while rendering fine detail at every scale — from the sweep of a city to the corner of a single street.

“Memory fades,” Watanave says. “Disasters replace each other. But if we connect the past to the present through technology, people can truly experience history.

A digital historian with gamer roots

Watanave’s path to becoming one of the world’s leading digital archivists was anything but linear. He trained as an engineer, then he worked at Sony in the early 1990s, right as 3D video games were exploding into mainstream culture. He was fascinated by the idea of creating immersive environments that people could enter and explore.

That sensibility stayed with him when he returned to academia. Instead of writing traditional history or designing flat infographics, he began experimenting with interactive, map-based experiences. His students collected survivor testimonies from the atomic bombings; he tagged the stories to precise street corners in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Anyone with an internet connection could click on a location, hear a voice, and see the world through someone else’s eyes.

The idea was radical at the time: Present history not as a narrative delivered from on high, but as a layered, participatory archive. It was also labor-intensive. Photographs had to be matched to buildings. Timelines had to be geolocated. Shadows, street angles, even the position of the sun in 1945 had to be accounted for. But the result was something no textbook could provide: immediacy.

“Young people today don’t watch long films or read long texts,” Watanave says. “But they play Minecraft, they explore in VR. If we want them to carry these memories forward, we have to use the media of their time.”

Enter Cesium

Pulling this off at scale, though, requires more than vision. It demands a platform that can handle massive datasets, render them in 3D, and deliver them to anyone, anywhere, on any device. After experimenting with tools like Google Earth, Mapbox, and ArcGIS, Watanave found his answer in Cesium, which was originally spun out of aerospace engineering and is now part of Bentley Systems.

Cesium’s innovation lies in its 3D Tiles format, which breaks down gigantic models — of entire cities or high-resolution photogrammetry of a single bridge — into streamable chunks. Instead of forcing users to download unwieldy files, Cesium streams just what you need as you move through a scene. That means an archive can be accessible globally, in real time, through a standard browser.

For Watanave, that scalability was decisive. His archives aren’t boutique VR demos shown to a handful of museum visitors. They’re public-facing, cloud-hosted experiences designed for students, journalists, and everyone else. “Cesium is open, it’s web-based, and it scales,” he says. “That combination is essential.”

The technology also integrates with VR headsets, the Unity gaming engine, and AI tools, giving Watanave’s small team the flexibility to prototype quickly. When his group needed fog effects to simulate the eerie atmosphere around a submerged Zero Reconnaissance Seaplane, they layered Cesium data with post-processing scripts. When coding got tricky, the team leaned on AI assistants like Google Gemini and ChatGPT to accelerate the work. This year, a special program featuring Watanave’s reconstruction of a Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Japan’s World War II fighter plane, lying on the seafloor. His team built the model using photogrammetry and 3D scanning, then deployed it in Cesium.

On screen, viewers can descend beneath the waves, glide around the corroding fuselage, and even surface to see how the wreck aligns with the nearby coastline. For the Expo 2025 in Osaka, the project is being presented in the United Nations Pavilion, allowing international visitors to step into a digital relic of war.

Without Cesium’s ability to handle enormous 3D datasets and bathymetric terrain, the project would have been nearly impossible to share widely. Instead, it runs smoothly in a browser — a global exhibit without walls.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, reimagined

Watanave’s most urgent work remains the Hiroshima and Nagasaki archives, which mark their 15th anniversary in 2025 — the same year the atomic bombings reach their 80th. Survivors are dwindling; the youngest are now in their late 70s. Preserving their voices has become a race against time.

Watanave’s renewed archives combine survivor testimony, archival photos, and 3D reconstructions, all layered onto Cesium’s globe. Users can navigate street by street, toggling between past and present, hearing voices tied to precise locations. A school child might stand virtually in front of what was once a classroom, listening to the words of someone who survived there eight decades ago. “The place and the memory together create empathy,” Watanave says. “It’s not abstract anymore. It’s real.”

This isn’t just academic. Teachers in Japan are already using the archives in classrooms. International exhibitions have carried them to the United Nations. And because they’re web-based, the archives can be accessed anywhere. (Watch the video here. Enter the Nagasaki Archive here. Enter the Hiroshima Archive here.)

From Ukraine to the classroom

Watanave’s work doesn’t stop with WWII. During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he and his students mapped bombed schools, destroyed housing blocks, and even the sinking of the Russian Moskva cruiser. They verified imagery using sun angles and shadows, then layered it into Cesium maps for public access.

The work was personal: “I imagined my daughter in those schools,” Watanave recalls. “That made it impossible to look away.”

The same methods have been applied to earthquakes in Turkey, flooding in Japan, and the unfolding conflict in Gaza. Each archive is different, but the principle is the same: make it explorable, make it global, and make it personal.

Looking ahead, Watanave imagines connecting these disparate archives into a global memory map: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Pearl Harbor, Ukraine, Gaza, natural disasters — all coexisting on a single Cesium globe. Visitors could toggle between times and places, seeing how humanity repeats and responds to catastrophe.

It’s ambitious, but the building blocks are already there. Cesium provides the technical substrate, while students, communities, and institutions provide the content. “We can democratize memory,” he says. “Anyone, anywhere, should be able to contribute and to learn.”

When history becomes interactive

What Watanave is building is more than a set of digital museums. It’s an argument about the future of memory in a digital age. Textbooks date, films fade, monuments crumble. But geospatial, explorable archives can persist and evolve, meeting new generations in the mediums they use.

For Cesium, it’s a showcase of what’s possible when this infrastructure technology is applied to humanistic ends. The same tiling system that helps satellites stream imagery can help a teenager walk through Hiroshima as it was in 1945 and watch video accounts of the bombing directly from the survivors.

That’s what makes this story resonate beyond academia. It’s about how a powerful technology, in the hands of a creative innovator, can reshape how we experience and remember history.

The Future of Digital Memory

In the coming years, Watanave wants to push further into VR, building on his new multi-user environments where entire classrooms can “walk” through history together. He imagines collaborative Cesium building workshops and AI-generated scenarios that further scale his work to cover more of history in greater detail.

At Expo 2025, his Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Zero Reconnaissance Seaplane projects will sit side by side in the UN Pavilion, a global stage for digital remembrance.

“As survivors pass away, these experiences are a great way for young people to understand their history,” he says. “My purpose is to use technology to help them feel that connection.”

Thomas Kohnstamm is a journalist and author. His latest novel, Supersonic, came out in February, and Publisher’s Weekly named it of the most anticipated literary fiction titles for Spring 2025.