Straight lines may be efficient, but in Barcelona, they’re practically a provocation. The chaotic and curvy forms of the city’s iconic buildings are now part of its identity — from the jagged columns of La Sagrada Familia, which stretch heavenward like an ancient stone forest, to the scaly roof of Casa Batlló, the modernist masterpiece nicknamed the House of the Dragon. As their architect Antoni Gaudí put it: “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.”

While Gaudí strayed from the straight and narrow, Ildefons Cerdà, the urban planner who oversaw Barcelona’s 19th-century expansion, also thought outside the box. His revolutionary design of the Eixample district trimmed the corners off street intersections, creating eight-sided blocks instead of perfect squares. These elegant octagons improved urban function as well as form, enhancing traffic flow, ventilation, and daylight across the cityscape.

The avant-garde spirit of Gaudí and Cerdà still burns bright in Barcelona. There’s not a straight line in sight on the W Hotel, the sail-shaped tower on the city’s beachfront that opened in 2009. Its shimmering, curvaceous façade appears to rise straight out of the Mediterranean, catching the brilliant sunshine and sea breeze. On July 8, the W Hotel is hosting Bentley’s Illuminate Barcelona, an exclusive gathering that brings together leaders from infrastructure, engineering, design and other areas to discuss the infrastructure sector’s most pressing needs. (You can still register!)

Today, Barcelona’s urban planners remain radically progressive and human-centered: they are reimagining the city as a series of “superblocks” — pedestrian-first zones that prioritize people and green space over cars and concrete.

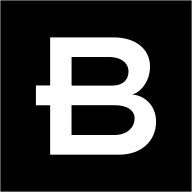

With so much, on display, I can be difficult to experience everything Barcelona has to offer. We’ve built for you an interactive experience using Cesium 3D geospatial technology so you can get an early start! Test it out below.

Eixample District

Unique to Cerdà’s design of Eixample (“expansion” in Catalan) is the cutting of corners at 45-degree angles — a feature called a chamfer. Cerdà, who trained as an engineer, predicted that steam trams would someday dominate the city and require long turning radii. He was wrong about the vehicle, but right about the physics: today’s drivers make good use of the extra room to maneuver. Cerdà also left space between buildings for gardens and green courtyards, which now offer residents a welcome respite from the city’s heat and bustle.

W Hotel

You can’t miss the 26-story W Hotel, known locally as Hotel Vela — the Sail Hotel. Designed by Spanish architect Ricardo Bofill, the luxury hotel sits on land reclaimed from the sea and juts dramatically into the Mediterranean. Its signature sail shape isn’t just aesthetic flair: the curved façade allows guests to enjoy both sea and city views from every room.

La Sagrada Familia

Gaudí replaced traditional flying buttresses with craggy, branching columns to give the basilica the feel of a stone forest. Like trees, the columns have irregular, organic shapes, thanks to his use of complex geometric forms like hyperboloids and helicoids. But there’s plenty of method to the madness. Gaudí used a hanging-chain model technique to design the structure — a kind of architectural magic trick involving strings and weights to model the church upside down. Flip the model upright, and the strings fall into place, revealing the ideal angles for columns and arches that naturally support the building’s massive weight.

Colón Column

Architect Gaietà Buïgas built the Colón (Columbus) Column at the lower end of La Rambla, Barcelona’s famous tree-lined boulevard, for the 1888 Universal Exposition. Historians claim the monument stands on the very spot where Columbus reported to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand after his first voyage to the Americas. Contrary to popular belief, his statue doesn’t point toward America, but out to the Mediterranean Sea.

Plaça Espanya

Plaça Espanya was conceived as a grand gateway for the 1929 International Exposition, held on Montjuïc — the squat hill that also hosted the Olympic Stadium, centerpiece of the 1992 Games (and until September 2025, the home ground of FC Barcelona). The square’s ornate fountain, designed by Gaudí collaborator Josep Maria Jujol, features three columns symbolizing Spain’s three seas: the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Bay of Biscay. Before its transformation, however, Plaça Espanya was better known for grim departures than glorious arrivals — it was the site of public hangings until the early 18th century.

El Peix

The Frank Gehry sculpture, on the city’s waterfront, was created for the 1992 Olympic Games. There’s no mystery about its inspiration: The sculpture looks like a fish, a nod to Barcelona’s maritime heritage and relationship with the Mediterranean Sea. Gehry’s team used advanced 3D modelling software to design and fabricate the sculpture, which has a curved, organic form, and features interlocking stainless-steel strips that shimmer like silvery-gold scales.

The Camp Nou

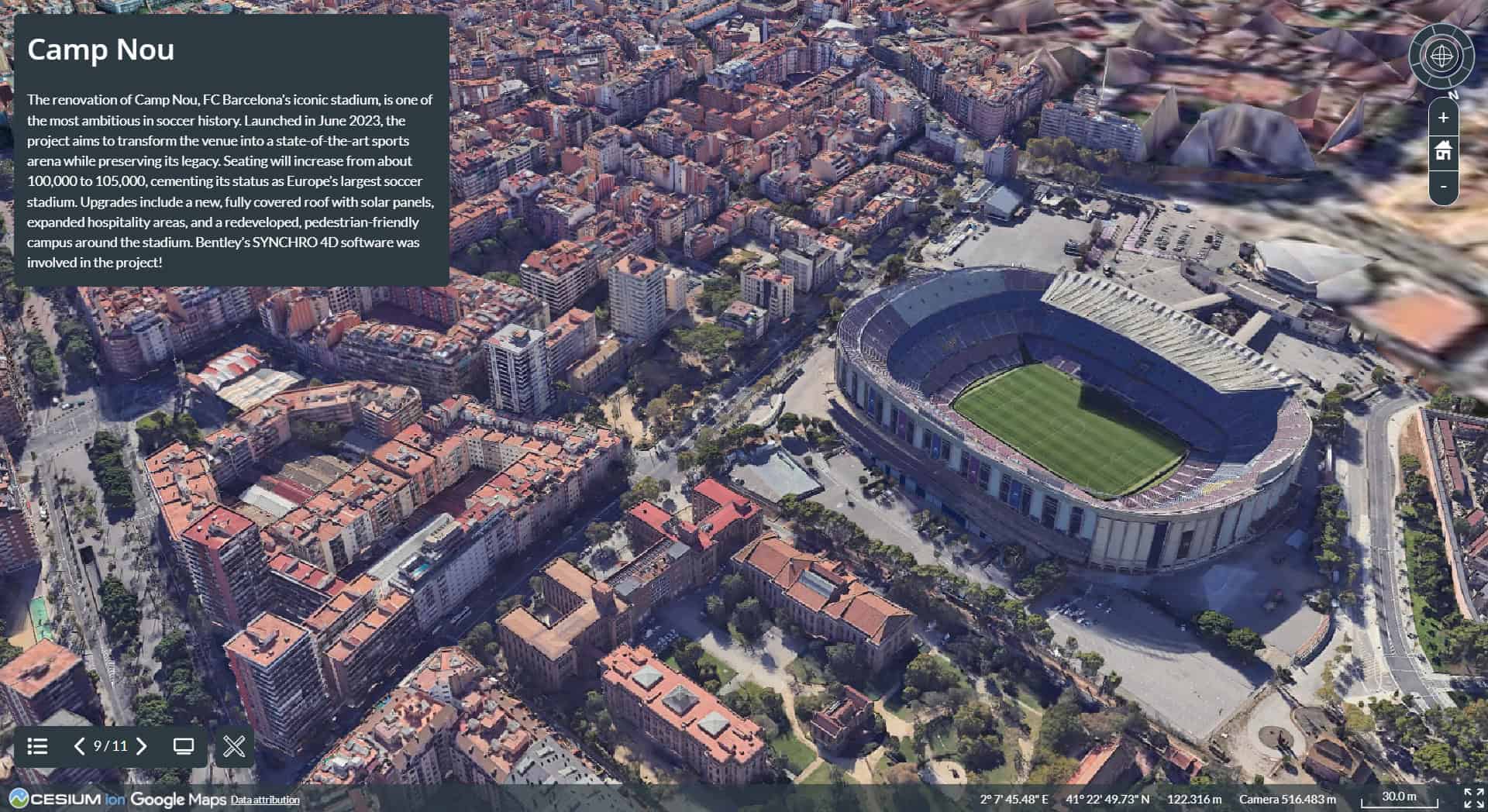

The renovation of Camp Nou, FC Barcelona’s iconic stadium, is one of the most ambitious in soccer history. Launched in June 2023, the project aims to transform the venue into a state-of-the-art sports arena while preserving its legacy. Seating will increase from about 100,000 to 105,000, cementing its status as Europe’s largest soccer stadium. Upgrades include a new, fully covered roof with solar panels, expanded hospitality areas, and a redeveloped, pedestrian-friendly campus around the stadium. Bentley’s SYNCHRO 4D software was involved in the project!

Montjuïc

Montjuïc’s name comes from the Catalan mont dels jueus — “Jewish Mountain” — named for the medieval Jewish cemetery that once occupied the site. At its summit sits Montjuïc Castle, a 17th-century fortress that played key roles in the War of the Spanish Succession and the Spanish Civil War. But the hill has long since shaken off its somber past. Today, it’s known for its cultural highlights: the National Art Museum of Catalonia, the Magic Fountain, and the Poble Espanyol open-air architectural museum. And the hill has left its mark elsewhere — stone quarried from Montjuïc was used to construct many of Barcelona’s landmarks, including the Cathedral and Santa Maria del Mar.

Temple Expiatori del Sagrat Cor

The basilica that crowns Mount Tibidabo looks like a triumph — but it began as a preemptive strike. Fearing a hotel or casino would be built on Barcelona’s highest peak, the city’s Board of Catholic Knights bought the land in 1886 and gifted it to Saint John Bosco, ensuring it would be dedicated to the Sacred Heart. But Tibidabo draws more than just pilgrims. The Sagrat Cor shares its perch with Spain’s oldest amusement park, opened in 1901. Among its steampunk-style rides is the Avió, a replica of the airplane that completed the first Barcelona–Madrid flight in 1927.

Chris Noon is a business reporter and foreign correspondent. He is based in Barcelona.

Christof Lorenz is a Cesium business development director for EMEA. He’s also a visual Cesium storyteller.