The Premier League is known as the Greatest Show on Earth, and it’s not just hype. The English soccer competition has a worldwide TV audience of around 3.2 billion people, from fans in Los Angeles who rise before dawn to support their clubs to Uganda’s Arsenal FC fanatics, who pray together for victory ahead of matches. Viewers are almost guaranteed 90 minutes of pure entertainment, with the Premier League boasting many of the world’s best players, a physical and attacking style of soccer, and stadiums typically packed to the rafters with passionate fans.

The on-screen thrills begin even before anyone’s kicked a ball. Belgium-headquartered Boost Graphics has built a series of high-definition flyby journeys of the Premier League’s 20 stadiums specially for the competitions. The stunning 3D videos, which Premier League broadcasters show during live games, also include highlights packages and news reels. They harness Cesium—the foundational open platform for creating powerful 3D geospatial applications that is now part of Bentley Systems.

Bright lights, big city

Starting in outer space, viewers nosedive through Earth’s atmosphere until the bright lights of a city rush up to meet them. Then they swoop smoothly and gracefully over streets and buildings, all rendered in crisp 3D, toward the game venue. Finally, viewers rise to hover over the stadium, like a majestic eagle.

Tim Van Dingenen, who heads Boost’s Technical Motion Design team, says the animations are a white-knuckle ride and a geography lesson. “Viewers can learn more about the area of England where the game is being played, and the journey there,” he says. “And we wanted their experience to look as good as something you could capture with a drone or helicopter.”

The Boost team has succeeded. Whether it’s the cozy seaside headquarters of AFC Bournemouth on England’s south coast or Newcastle United’s hilltop fortress in northern England, the animated flybys offer a keen sense of place in the most fun way possible.

Getting Unreal

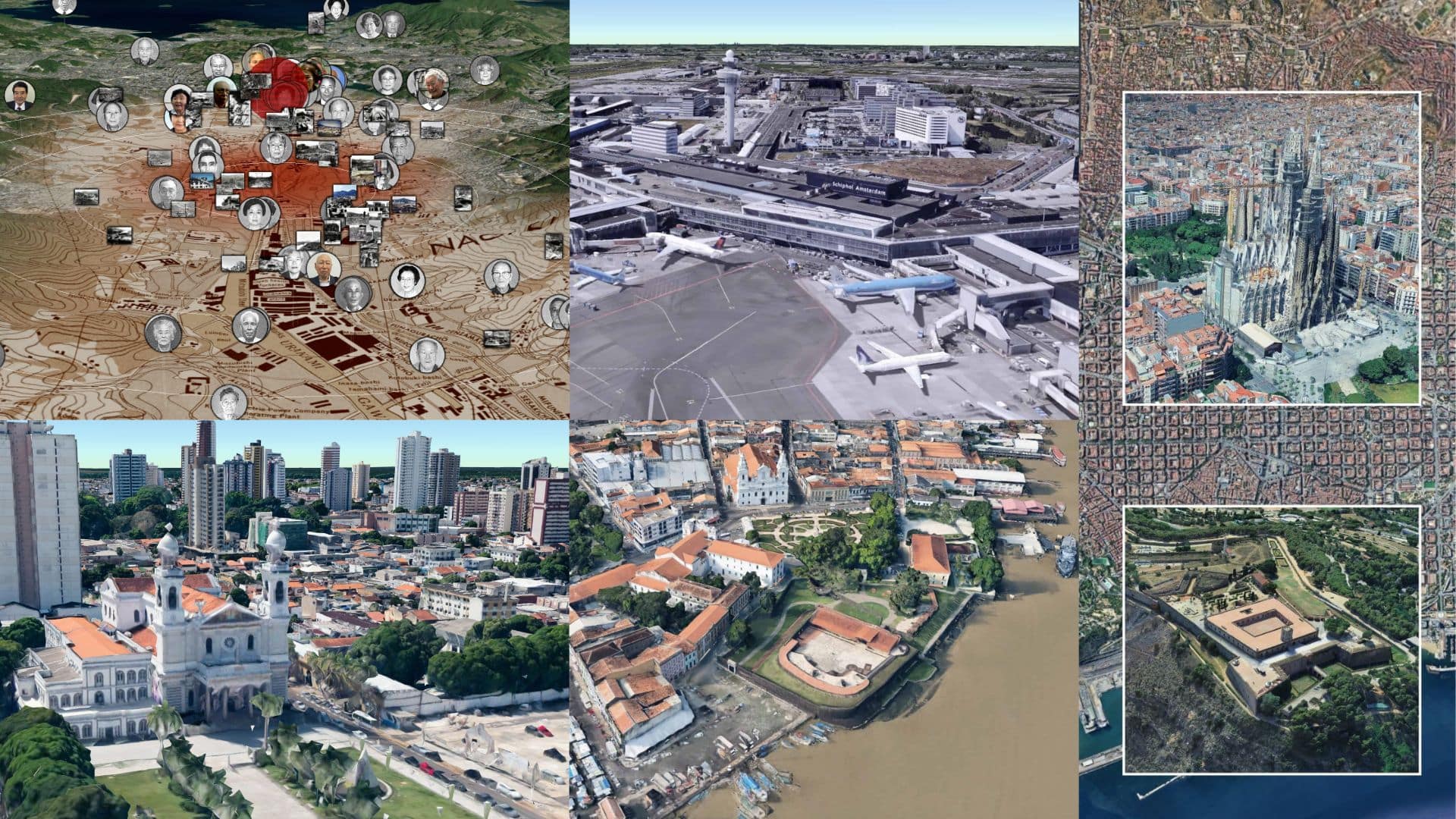

Digital twin of London skyline powered by Bentley’s iTwin and Cesium’s 3D geospatial technology.

Digital twin of London skyline powered by Bentley’s iTwin and Cesium’s 3D geospatial technology.There’s a serious amount of cutting-edge technology behind the infotainment, too. Boost used Cesium for Unreal, a powerful tool for creating photorealistic interactive experiences. The plug-in combines the 3D geospatial capabilities of Cesium with the high-fidelity rendering power of Unreal Engine, the world’s most successful videogame engine. “Cesium for Unreal combines the visualization of massive, high-resolution 3D geospatial datasets enabled by 3D Tiles, with the photorealistic high-fidelity rendering of Unreal Engine,” says Shehzan Mohammed, Bentley’s senior director of platform and developer community. “By connecting creators across industries to the world-building tools of Unreal Engine in the context of real-world data, like Google Photorealistic 3D Tiles, Cesium for Unreal helps blur the line between the physical and digital worlds.”

“We couldn’t have done this without Cesium,” adds Van Dingenen, whose team is using the platform to build a new batch of animations for the 2025-26 Premier League season, which kicks off on August 16.

A stunning debut of work that gets easier

Boost Graphics debuted on the world’s TV screens in 2015. Wielding 3D virtual maps, a game engine, and open-source satellite data, the Belgian company built virtual racetracks for European and U.S. broadcasters showing the Tour de France, the world’s most famous cycling race.

While the animations were stunning, making them was an uphill slog. Boost downloaded a mix of satellite and open-source terrain, landscape, and land mass data, including buildings, forests, and water features. “It took around 30 hours to download each of the race’s 21 stages, and it was quite expensive to set up and change,” says Van Dingenen. Once downloaded, the data needed to be combined and loaded into an animated scene, requiring 120 gigabytes of memory. Boost’s revenues were also limited by the three-week duration of the event.

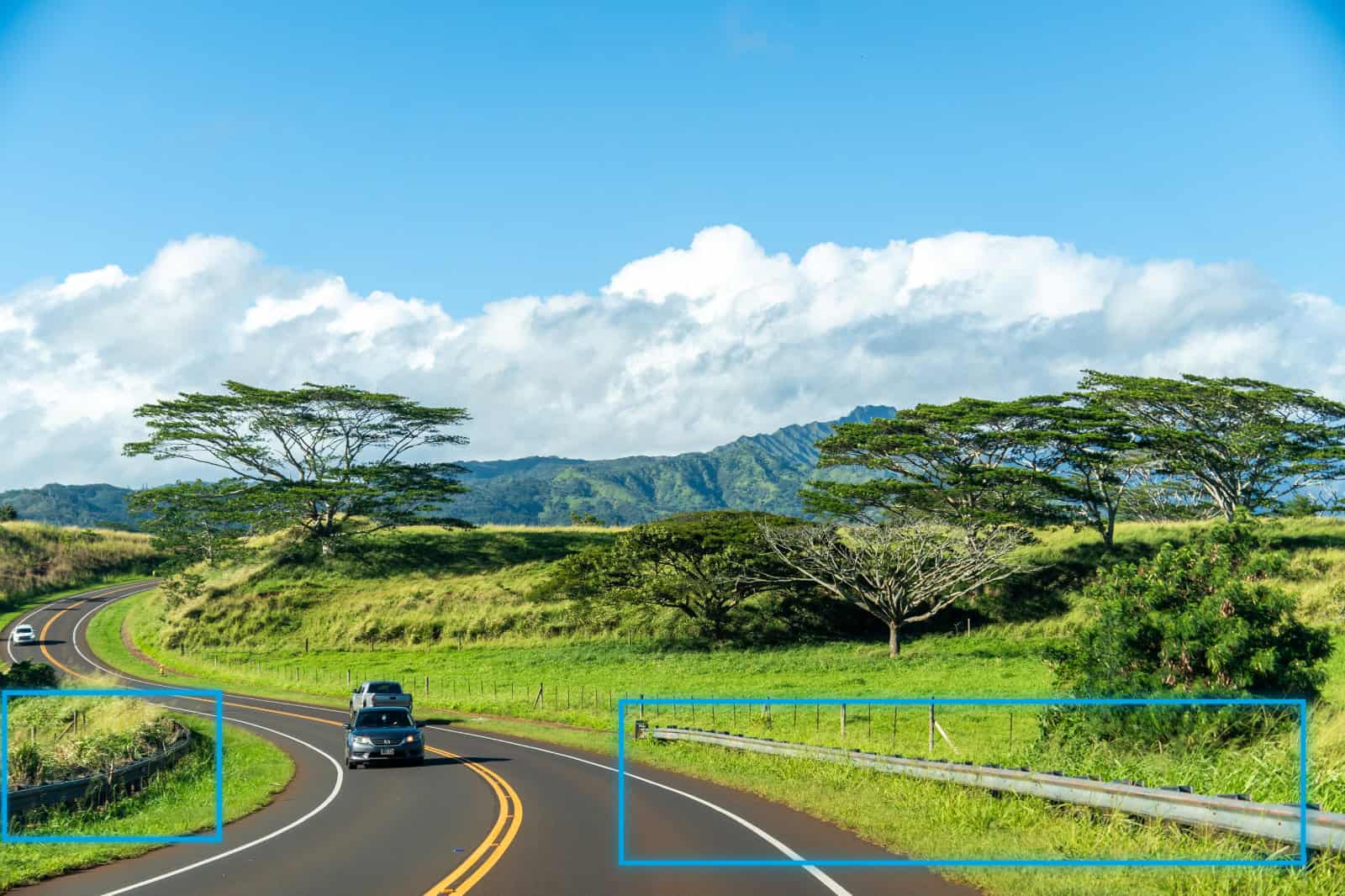

Boost’s Premier League locators come in two versions, tailored for use based on timing of the game. Courtesy Boost Graphics.

Boost’s Premier League locators come in two versions, tailored for use based on timing of the game. Courtesy Boost Graphics.Boost’s work became easier in late 2021, around the time that Google Earth, now part of the Google Maps platform, leaped forward to blend aerial photography, satellite imagery, 3D topography, and street views into a real-world canvas. Van Dingenen says the tech giant had just replaced most of the manually modeled buildings on its popular platform with automated, photogrammetric reconstructions, which were enabled by aircraft flying over urban areas, taking photos at 45-degree angles to capture the vertical surfaces of buildings. “We began wondering how we could implement this nice-looking building data in our products,” he says.

The team holed themselves up in the studio and emerged a few days later with a prototype of a soccer stadium flyby. “It wasn’t perfect, but it worked fine, and it looked great,” says Van Dingenen. In early 2022, Boost showcased the demo at a London-based industry event. Belgium’s Flemish-speaking news channels began knocking at Boost’s door. They wanted similar flyby animations for their rolling bulletins, allowing them to parachute viewers into the heart of the action. In June 2023, a year after Boost’s London showcase, Van Dingenen’s phone rang.

“It was the Premier League, and they also wanted the flyovers,” he says.

A race against time

There was a catch. The Premier League wanted the animations before the start of the 2023-24 season, which was just two months away. They also needed at least 80 videos: Day and night versions for all 20 stadiums, to simulate afternoon and evening kick-offs, and 20- and 45-second cuts of each.

It was a tall order, but Boost’s developers had a favorite new toy: Cesium. This enabled Boost, using the 3D Tiles format created by Cesium, to efficiently stream massive, detailed 3D datasets of cities across the world.

Taking advantage of Google’s open Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) and Cesium technology, Boost could build beautiful renditions of cities, down to the bricks and beams of individual buildings and stadium terraces. The speed of the work made them feel like alchemists. “You put in the GPS coordinates of where you want to work, and Cesium just immediately loads in everything,” says Van Dingenen. “It was really nice-looking.”

A sprinkling of magic

Boost’s team working with Google’s Photorealistic 3D Tiles in Unreal Engine. Courtesy Boost Graphics.

Boost’s team working with Google’s Photorealistic 3D Tiles in Unreal Engine. Courtesy Boost Graphics.But the Boost team needed to bring their visualizations to life, which was tougher than it looked. Viewers break through Earth’s atmosphere at supersonic speed and slam on the brakes when the cityscape rushes into view. “We [are] decelerating very quickly, which made it hard to animate,” says Van Dingenen. The developers carefully designed a kind of digital dolly, varying the velocity and angle of attack for their journey for maximum drama.

To ensure the smooth unspooling of the images, the Boost team needed to scale down the detail of their immersive 3D digital experiences. But they needed to shrink carefully, or they’d lose quality. Fortunately, they’ve found a sweet spot.

To add an extra sprinkling of lifelike magic, the Unreal game engine uses sophisticated rendering technology to replicate natural light, shadows, and fine surface detail. “It gave us loads of adaptability,” says Van Dingenen, referring to the ease of varying lighting, weather conditions, and season. He demos Boost’s night flight over Everton Stadium, the dockside home ground of Everton FC, that features streetlights shimmering off the River Mersey.

The Boost team made their Premier League deadline, with time to spare. “We did about 90 days of work in 30 days,” says Van Dingenen. He estimates that Cesium saved Boost tens of thousands of dollars compared to building the animation from scratch.

Soccer fans may soon see more of Boost’s work, with the Belgian company a candidate to produce the stadium flyby for a major European final. “There’s clearly demand for this product, and it’s good fun to do,” says Van Dingenen. “It’s very easy to change location, and the Cesium plug-in makes everything adaptable, so there’s no stopping us.”