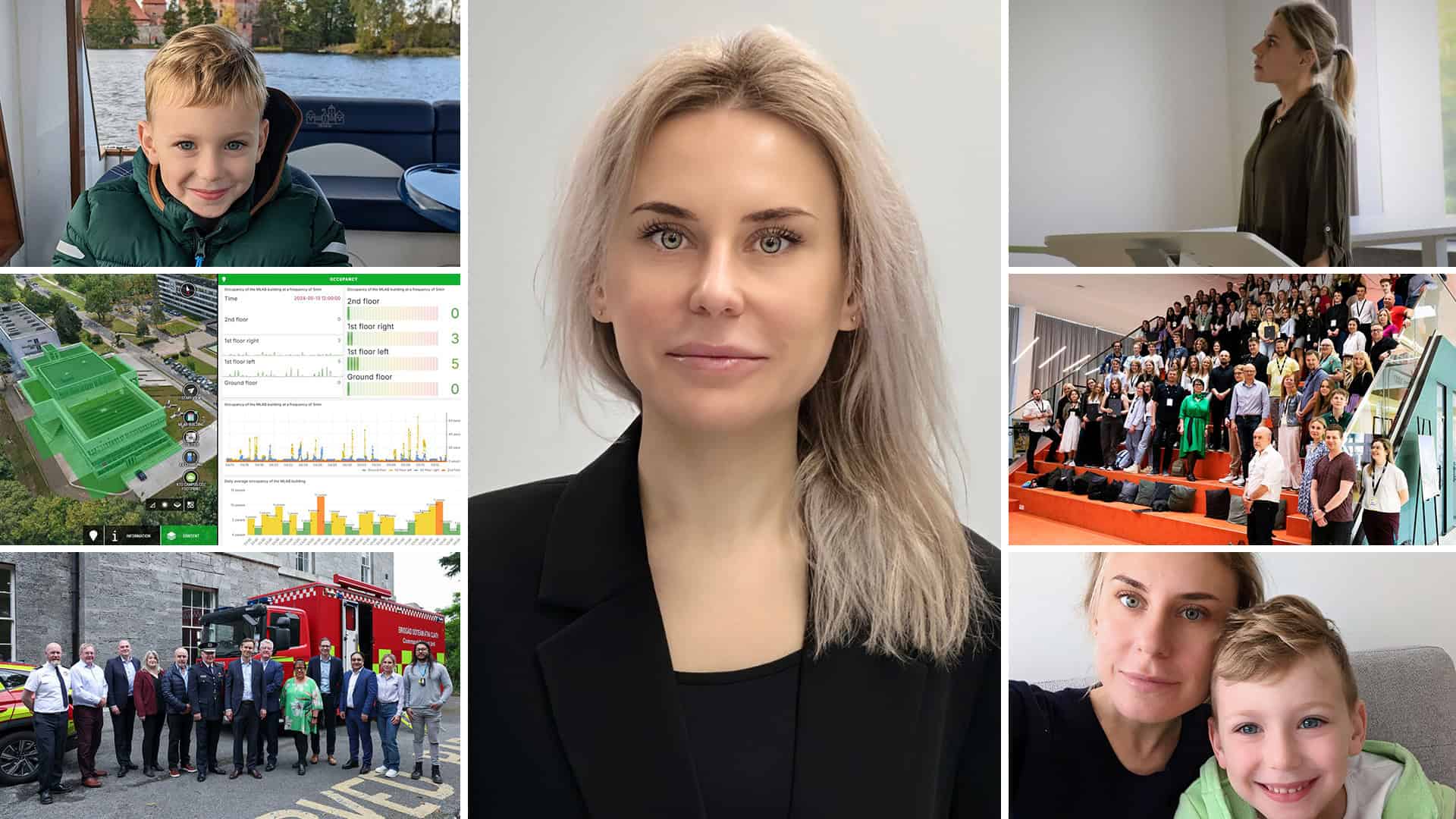

Iryna Osadcha’s leap of faith from Kyiv to Kaunas is a story of personal fortitude and a new-found professional calling to strengthen urban resilience

When Russian tanks crossed into Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Iryna Osadcha’s life, like that of so many others, was irrevocably transformed. Osadcha was working as a civil engineer while pursuing a Ph.D. on modular construction part-time at Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture. But when the invasion of her home country began, she faced a decision that no academic or field handbook covered: whether to leave behind her home, her work, and her husband to seek safety abroad with her 4-year-old son, Yakiv. And decide she did — quickly. “We were shocked and lost,” she recalls. “It wasn’t clear what was going to happen, but I knew we had to move fast.”

That first morning, Osadcha took her son and fled to central Ukraine, seeking refuge with her mother-in-law. “I was very afraid. I didn’t understand what was going on or how long it would last. I just instinctively knew we needed to get out,” she says. That same day, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, declared martial law and imposed a travel ban on men eligible for military service, meaning Osadcha’s husband would have to remain behind.

“We were shocked and lost,” said Osadcha, who escaped with her son, Yakiv, to Kaunas, Lithuania. “It wasn’t clear what was going to happen, but I knew we had to move fast.”

“We were shocked and lost,” said Osadcha, who escaped with her son, Yakiv, to Kaunas, Lithuania. “It wasn’t clear what was going to happen, but I knew we had to move fast.”As the invasion upended Ukraine, Osadcha’s own path was similarly transformed. She didn’t know it yet, but her academic career would soon shift from modular construction to a field with far-reaching impact: digital twins. These virtual, data-driven replicas of real-world infrastructure assets are reshaping how cities confront crises – from wildfires and floods to missile strikes. For Osadcha, the technology would offer something more personal: a way to contribute to the reconstruction of war-torn countries like her own.

In the days that followed her departure from Kyiv, Osadcha emailed about 50 universities across Europe, explaining her situation and asking for help. Responses were sparse and non-committal. “Some universities said, ‘Yes, you can come, and then we will see what we can do.’ But I had a child to think about, and little money. I needed something concrete,” she says.

One of Osadcha’s emails landed in the laptop of Andrius Jurelionis, dean of the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Architecture at Kaunas University of Technology (KTU) in Lithuania. “Osadcha’s message was my first from Ukraine,” says Jurelionis, who was traveling at the time. “I just responded: ‘We will help you in any way we can.’”

Jurelionis quickly found an organization to help transport Osadcha and her son because she didn’t have a car. “It was a really, really big leap of faith for Iryna,” says Jurelionis, noting that the university’s offer wasn’t an isolated act. “All of Lithuania was mobilizing to help Ukraine,” he says.

Osadcha traveled with nothing more than her son and a medium-sized backpack. “It was a mess at the border – so many people – but we crossed safely, and Andrius met us in Kaunas and took care of everything.” They were settled into a dormitory room provided by the university. “People were very kind to me at the university and at the faculty, and so organized,” she says. “They helped arrange kindergarten for my son.”

“People were very kind to me at the university and at the faculty, and so organized,” says Osadcha, here pictured with KTU colleagues.

“People were very kind to me at the university and at the faculty, and so organized,” says Osadcha, here pictured with KTU colleagues.When Osadcha arrived at KTU, she began with a six-month internship under a temporary scheme to support Ukrainians seeking refuge. It was a chance to catch her breath and recalibrate. It was during this time that she co-authored a paper with her still-employer in Ukraine, the Research Institute of Building Production in Kyiv, focused on using a Building Information Modeling-based approach to assess the structural stability of large-panel buildings damaged by military actions. “It was tragic, but we had material for this paper because of the war,” she explains.

Inspections of buildings in Kyiv damaged by missile strikes had to be done with extreme caution. “Inspectors can’t always go inside damaged buildings because you don’t know how stable they are,” she says. Instead, drones were used to create a visual record of the damage. “Based on this, you can decide whether to repair, rebuild, or demolish.” It’s a crisis-driven approach that could have wider applications for post-disaster assessment of buildings around the world, including earthquake-hit regions.

Before the war, Osadcha’s career had followed a steady path. She earned her degree from Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture, then she spent three years as a building surveyor on large construction sites, not at all put off by the male-dominated environment. “Big construction sites, working outside in all weather conditions, you’re always dirty,” she says.

She later took a role at the State Research Institute of Building Constructions, where she was tasked with monitoring buildings that might be undergoing some distortion due to nearby construction projects—skills that would later prove invaluable at KTU. During this time, Osadcha also began pursuing a Ph.D. on modular construction, a popular prefabrication method used for residential buildings in Ukraine.

But if Osadcha wanted to continue her academic career after fleeing Ukraine, she would need a new Ph.D. topic. Her two years of research on modular construction, like her old life, had to be left behind. “We had to find the topic that Iryna could work on, that is linked to the research activities in our faculty, and where we can support her work,” Jurelionis says.

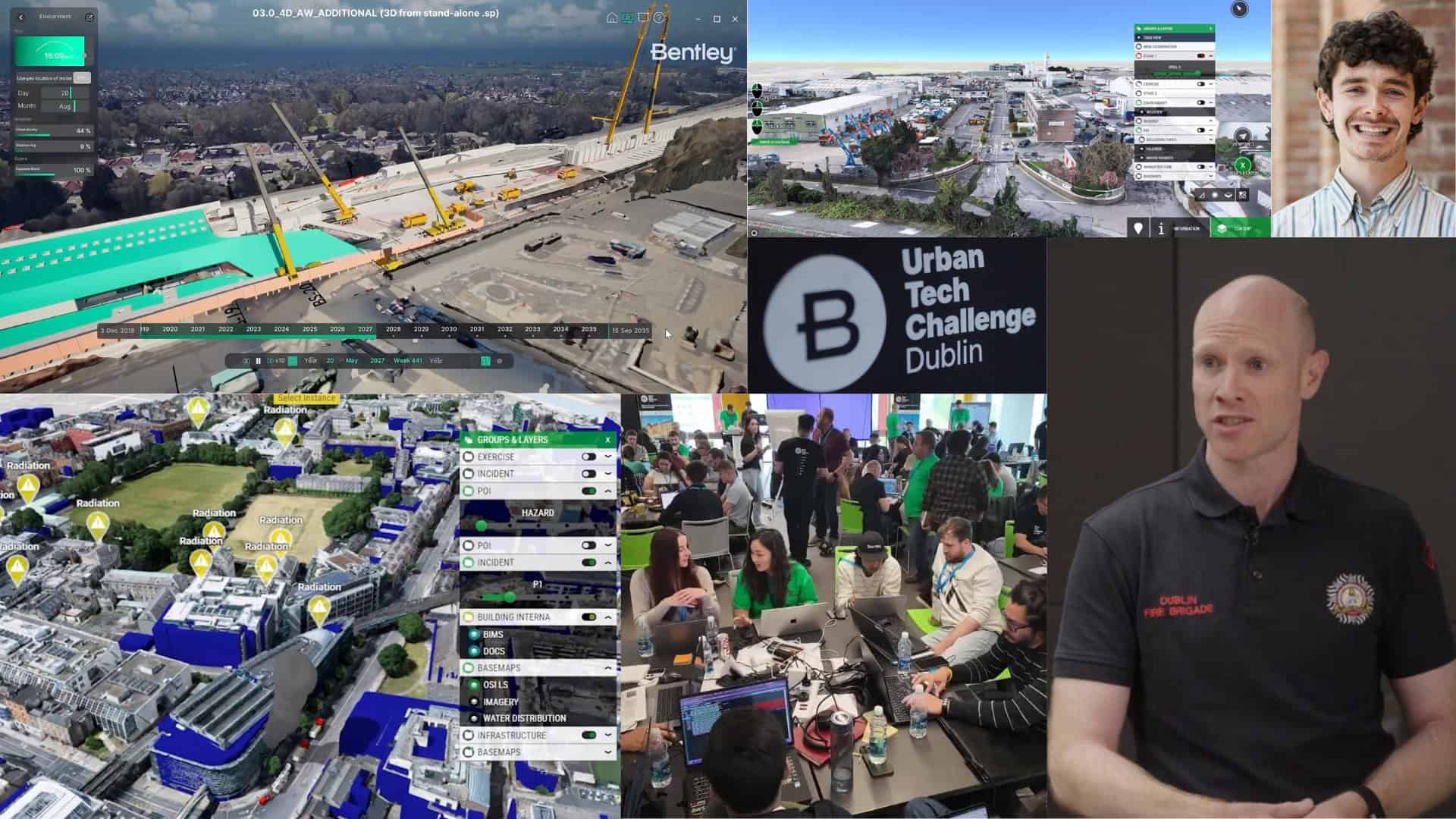

A digital dashboard showing occupancy data for a building on the Kaunas University of Technology’s (KTU) campus.

A digital dashboard showing occupancy data for a building on the Kaunas University of Technology’s (KTU) campus.She arrived at KTU at a time when the university was transforming into an educational leader in the digital transformation of civil engineering. The KTU Center for Smart Cities and Infrastructure launched in 2019, and it collaborates with Bentley Systems, the infrastructure engineering software company and a leader in digital twins, and other industry partners to develop digital twins for both the KTU campus and the city of Kaunas. These digital twins help design everything from energy-efficient buildings to emergency response plans. By integrating digital twins into student learning and city planning, KTU is shaping a new generation of engineers equipped to tackle global infrastructure challenges. Osadcha’s new Ph.D. focus, with Jurelionis as her supervisor, is digital twins, with an emphasis on emergency response and urban resilience.

As Ukrainian cities were being devastated by war, Osadcha’s research aims to develop better tools for post-disaster recovery and rebuilding in a range of contexts. At KTU, she is focusing on how best to keep the geometry of digital twins accurate and up-to-date – no small challenge in dynamic, unpredictable environments like conflict zones or disaster-stricken cities. She is also studying how to use digital twin architecture for emergency management.

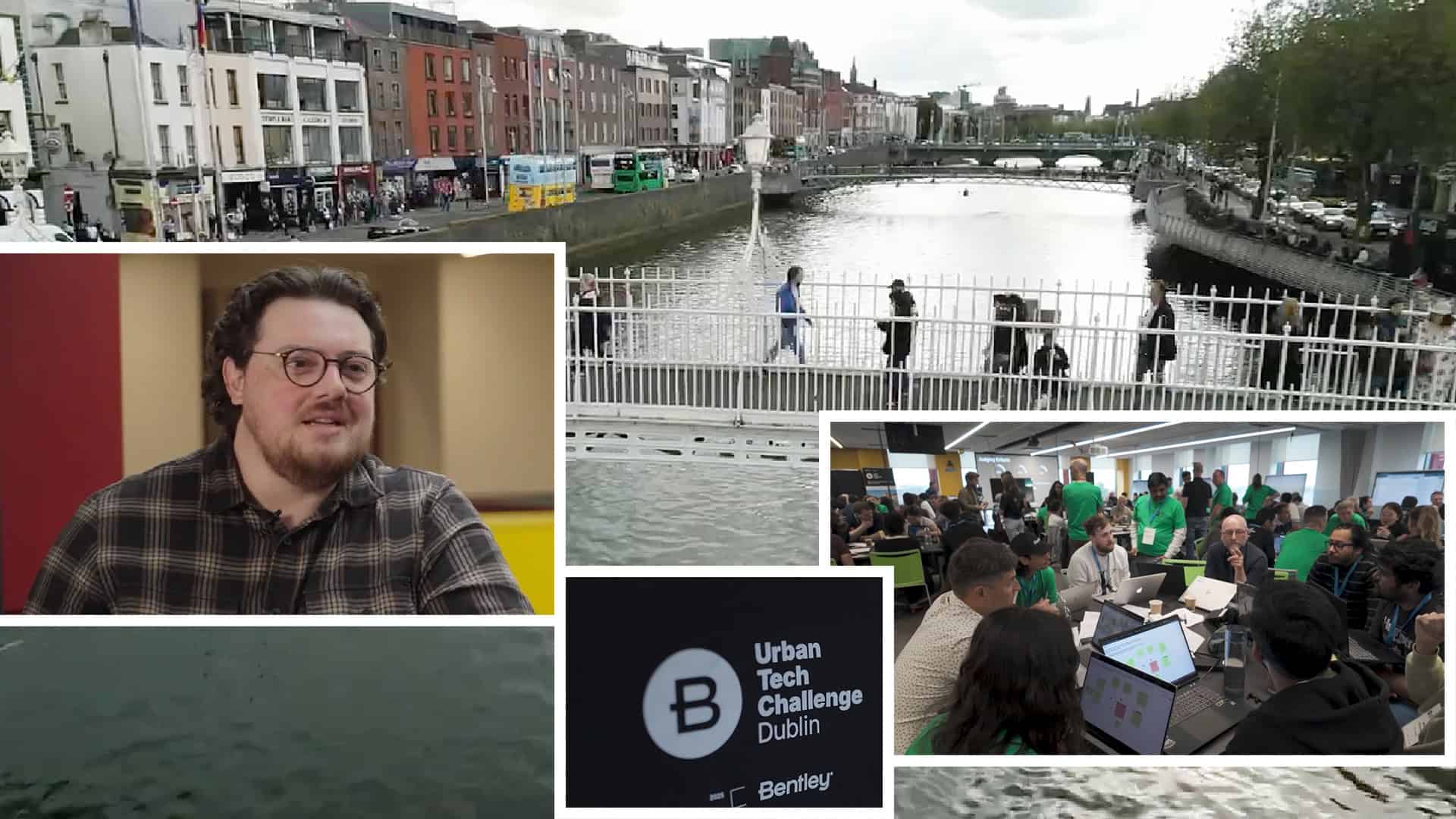

Bentley Chief Executive Officer Nicholas Cumins (center), Jamie Cudden, Smart City Program Manager at Dublin City Council (fourth from the right) and Iryna Osadcha (second from right) with the Dublin Fire Brigade.

Bentley Chief Executive Officer Nicholas Cumins (center), Jamie Cudden, Smart City Program Manager at Dublin City Council (fourth from the right) and Iryna Osadcha (second from right) with the Dublin Fire Brigade.While Osadcha’s Ph.D. is state-backed, Bentley co-funds her research through a donation. This relationship also enabled Osadcha to spend several months at Dublin City University in Ireland – another university developing a pioneering digital twin ecosystem in partnership with Bentley. She collaborated with the Dublin Fire Brigade. “It was fascinating to see how they are using digital twins to improve pre-incident planning and emergency response strategies,” she says.

Throughout the personal and professional upheaval, Osadcha has shown remarkable resilience. Among her challenges has been pursuing a demanding Ph.D. path in foreign languages. She says she struggles with both English and Lithuanian. “When I first moved, I spoke like a 3-year-old child,” she says. “But I just knew I needed to do it.”

Nearly three years since Osadcha’s escape to Lithuania, Jurelionis has nothing but admiration for her work and steadfastness. “First and foremost, Osadcha is a fighter. I can only say the best words about the quality of her work, and she always manages to maintain her optimism and positivity, even in dark circumstances.”

Osadcha’s appreciation of KTU and Jurelionis is equally clear. “He helped me more than anyone else in my life before – I don’t know if I could have done this without Andrius,” she says.

For Osadcha, the war has been both a tragedy and a turning point. “The war affects me, every day. My husband, family and friends are still in Ukraine,” she says. Does Osadcha think she’ll return to Ukraine after the war? “Yes,” she says, pausing, then adds, “probably more yes than no.”

For now, Osadcha is focused on completing her Ph.D. over the next two years. In early 2025, she will also join several dozen international Ph.D. students and early career researchers for KTU’s “Ph.D. Spring School,” led by Jurelionis. The participants will focus on urban digital twins, using Cesium for 3D geospatial visualization and Bentley’s iTwin platform “to create digital twins for more resilient, future-proof cities and infrastructure,” he says.

Osadcha’s story is also one of courage and commitment to rebuilding—not just her own life, but the systems and structures that support communities in crisis. Through her work with KTU, she is forging a bridge between her past experiences in Ukraine with a future of new possibilities.

“Life has changed so much,” she says. “But I hope what I’m doing now will make a difference—not just for me, but for others too.”

Find out more about Bentley’s community engagement here.