Some of the most famous inventions were happy accidents. In 1827, English pharmacist John Walker was puttering around at home when he clumsily scraped a chemical-coated stick across his hearth, which burst into flames, sparking the idea for the friction match. A century later, Scottish microbiologist Alexander Fleming returned from vacation to an untidy lab and noticed a strange mold in a petri dish, which he called “penicilin.”

But most groundbreaking discoveries aren’t so serendipitous. The world’s architects and engineers have spent centuries meticulously advancing the science of designing and building bridges, roads, dams and other infrastructure. Their work is deliberate, iterative and empirical. It builds on the knowledge and insights of those who came before them.

Their journey started with a letter from the Old Babylonian Empire, which ended about 3,600 years ago and commonly used clay tablets to record and share information. The letter “documents the drawing of architectural ground plans,” according to historians. More than 3,000 years later, Leonardo da Vinci drew on paper stunning conceptual plans and sketches for buildings, bridges, and cities. A few hundred years later, at the start of the Industrial Revolution, French mathematician Gaspard Monge invented descriptive geometry, a system that allowed architects to display three-dimensional objects on two-dimensional surfaces. It became the foundation of technical drawings, and engineers still use it today.

On the 40th anniversary of Bentley Systems, we are also celebrating engineering innovations. Take a look at our list.

A matter of perspective

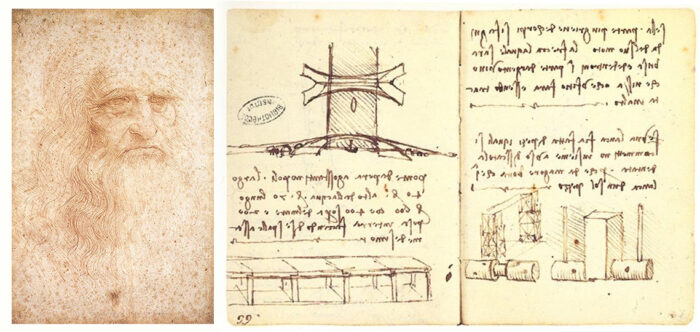

Leonardo Da Vinci self-portrait (left), and pages from Da Vinci’s notebook showing technical drawings for a bridge and mirrored handwritten notes (on the right).

Leonardo Da Vinci self-portrait (left), and pages from Da Vinci’s notebook showing technical drawings for a bridge and mirrored handwritten notes (on the right).Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Da Vinci is perhaps most famous for painting the Mona Lisa, but the Italian polymath was also one of the world’s first technical drawing experts. Many of his notebook sketches were visions of the future. For example, Da Vinci’s plan for the city of Imola reveals a civil engineer’s eye for function in its depictions of canals, grading and surrounding farmland, while his concept of a bridge that would cross the Bosporus Strait reveals an architect’s feel for form, scale and perspective. Like a good mathematician, Da Vinci always showed his proof, such as when he included calculations on dimensions and materials in his blueprint for a tile and shingle roof.

The French connection

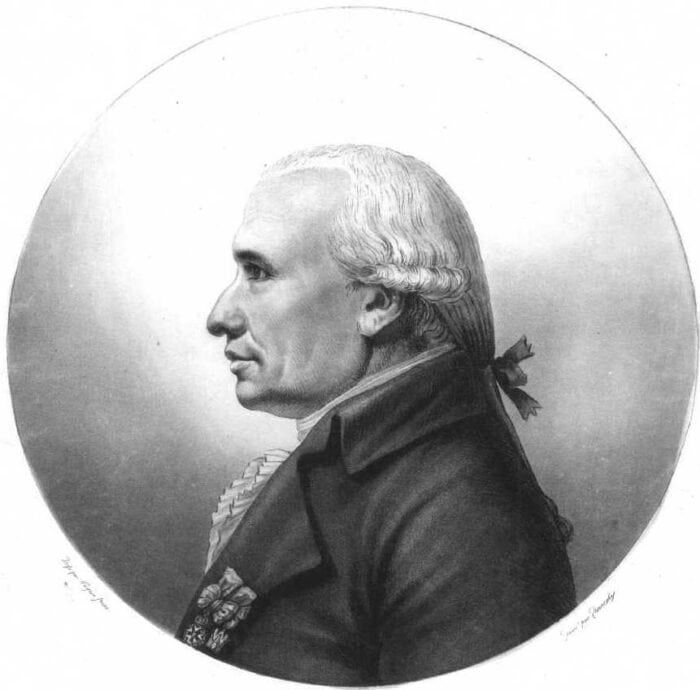

Profile portrait of French mathematician Gaspard Monge.

Profile portrait of French mathematician Gaspard Monge.Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Da Vinci may have etched a rough outline for the future of technical drawing, but it was Monge who filled in the blanks. In 1764, the brilliant young Frenchman made a large-scale plan of Beaune, the Burgundy town and wine destination that was his birthplace. Word spread quickly throughout the engineering community, and Monge secured a plum job as a draftsman for the French royal armaments factory in the northern town of Mézières. A year into the job, Monge made his mark, laying out the first rules of descriptive geometry. This allowed for orthographic projection or the representation of three-dimensional objects in two dimensions.

Anglo-French relations were distinctly uncordial at the time, so Monge’s work remained a military secret until 1794. But it wasn’t long before the likes of Marc Isambard Brunel, the French-British father of 19th-century engineering giant Isambard Kingdom Brunel, chief engineer of England’s Great Western Railroad, were adopting Monge’s methods in their work, bringing a new scientific rigor to their profession.

Back to the drawing board

Despite Monge’s breakthroughs, technical drawing was still painstaking work, requiring architects and engineers to spend hours hunched over their blueprints with various measuring instruments, often by candlelight. The arrival of the drafting machine in the early 20th century lightened their manual and cognitive load, if not the gloom where they toiled. Invented by Charles H. Little in 1901, the machine consisted of a pair of scales mounted to form a right angle on an articulated protractor head, which could move freely across the drawing board. The device was “accurate in operation, but relatively light in appearance and construction,” Little noted in a patent for his machine, which he received in 1913. The enhanced technical and ergonomic setup was a game-changer, allowing engineers to draw and measure smoothly, and banishing their fumbles with loose ruler squares and protractors to the past. It’s important to note that a different person, George Ring, received a patent for the modern drafting table in 1905.

OK, computer

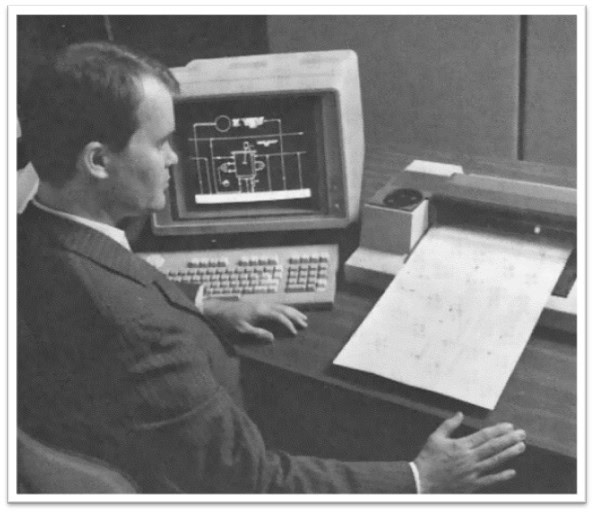

Computer-aided drafting (CAD) with MicroStation, 1986.

Computer-aided drafting (CAD) with MicroStation, 1986.Pencil and paper remained the main tools of draftsmen throughout most of the 20th century, until the groundwork was laid for their transition to computer-aided design (CAD) in the years after World War II. The story begins in 1954, when Patrick Hanratty, a veteran of the Korean War, discovered a talent for science while readjusting to civilian life in his hometown of San Diego, California. Despite having no college degree, Hanratty soon found work as a computer programmer with a local aircraft manufacturer. Hanratty was a quick study, and it wasn’t long before General Electric Company, which was developing numerical control software packages, came knocking for his services.

In 1956, Hanratty took the lead on a company project called the Program for Numerical Tooling Operations, or PRONTO, which aimed to give a computer automatic control of tools. PRONTO was a roaring success and became the world’s first computer numerical control (CNC) programming system. Its code later became the basis of computer aided design (CAD), the software that revolutionized the engineering, architecture and manufacturing landscape. CAD boosted the productivity of users, improved the quality of designs and optimized communication between project teams. By some estimates, around 70% of all 3D mechanical CAD/CAM systems available today can be traced back to Hanratty’s 1957 code.

Rise of the machines

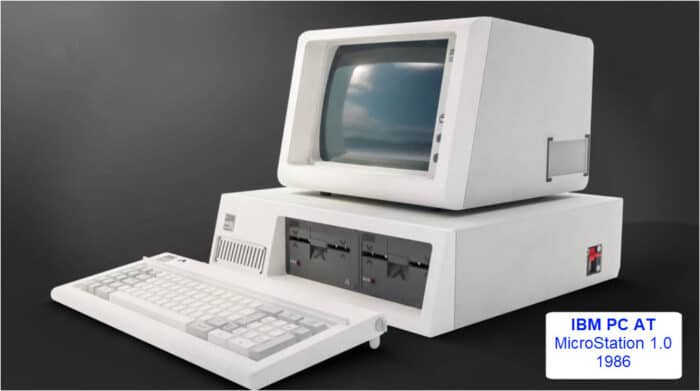

An IBM PC AT with an attached monitor, keyboard, and dual floppy disk drives. A label indicates it is running MicroStation 1.0 from 1986.

An IBM PC AT with an attached monitor, keyboard, and dual floppy disk drives. A label indicates it is running MicroStation 1.0 from 1986.The 1980s saw the arrival of serious computing muscle in the engineering profession in the form of Virtual Address eXtension and VAX-based workstations. The devices look clunky compared to today’s desktops and tablets, but they provided the computational heft for more complex calculations and larger datasets. (Bentley also used VAX machines early it its history. PseudoStation ran on a VAX computer. Its successor, MicroStation moved computer design work to the desktop and launched Bentley on its successful journey.) Instrumental to the creation of the machines was Gordon Bell, a man dubbed “the grandmaster of computer architecture” by Electronic Engineering Journal earlier this year. Bell, who hailed from a small town in rural Missouri, was a child prodigy: At age 12, he was wiring local houses and farms under the federal Rural Electrification Association program. After attending the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and earning a Fulbright scholarship teaching in Australia (during which he devised special computer code to propose to his wife), Bell landed a job at Massachusetts-based Digital Equipment Corp (DEC). There, he wrote software for the devices that would make DEC famous: minicomputers. Another stint in academia followed, then Bell returned to DEC in 1972 to spearhead the mission to produce a next-generation minicomputer, which duly became the legendary 32-bit VAX.

Digital twins

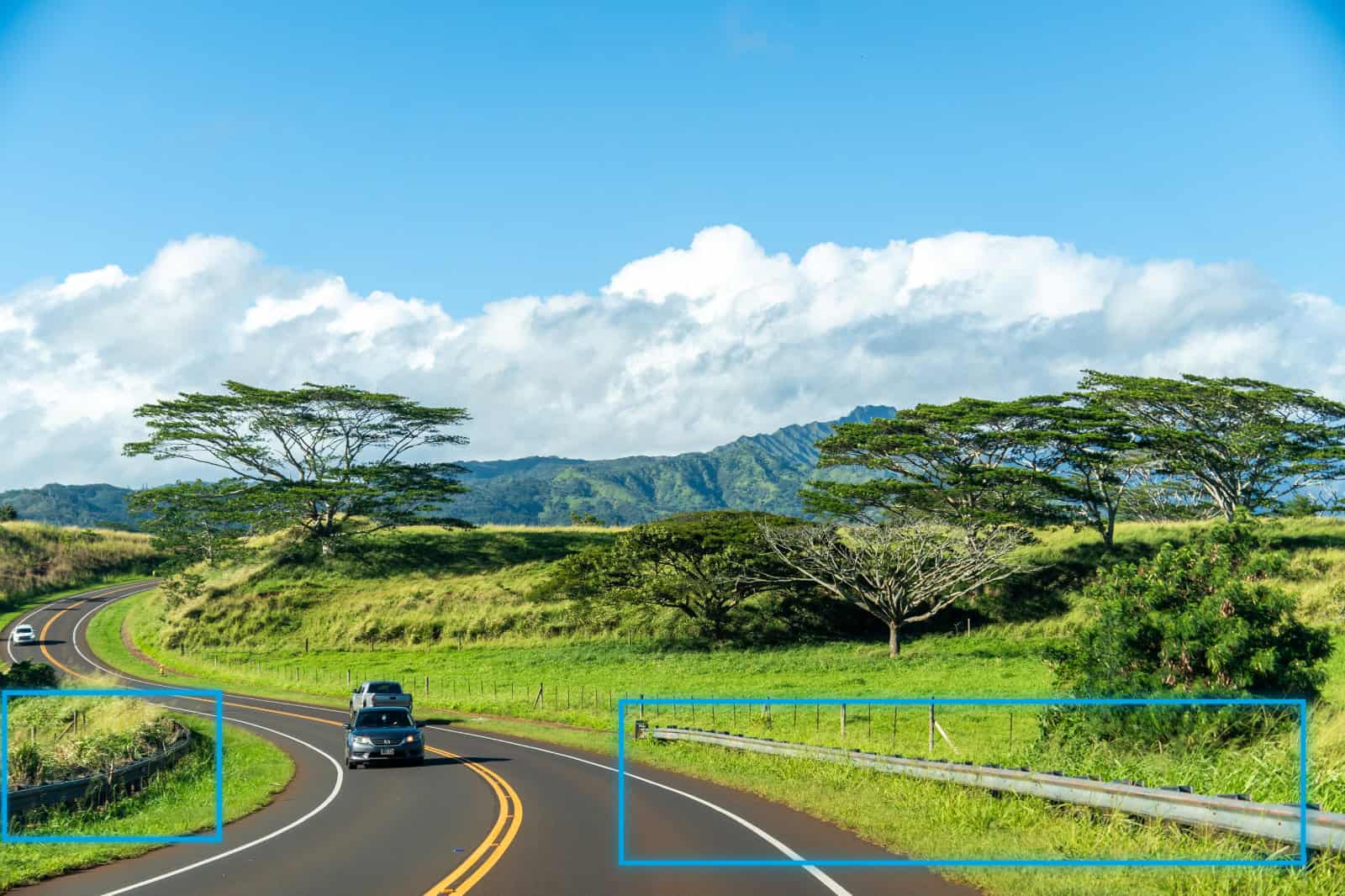

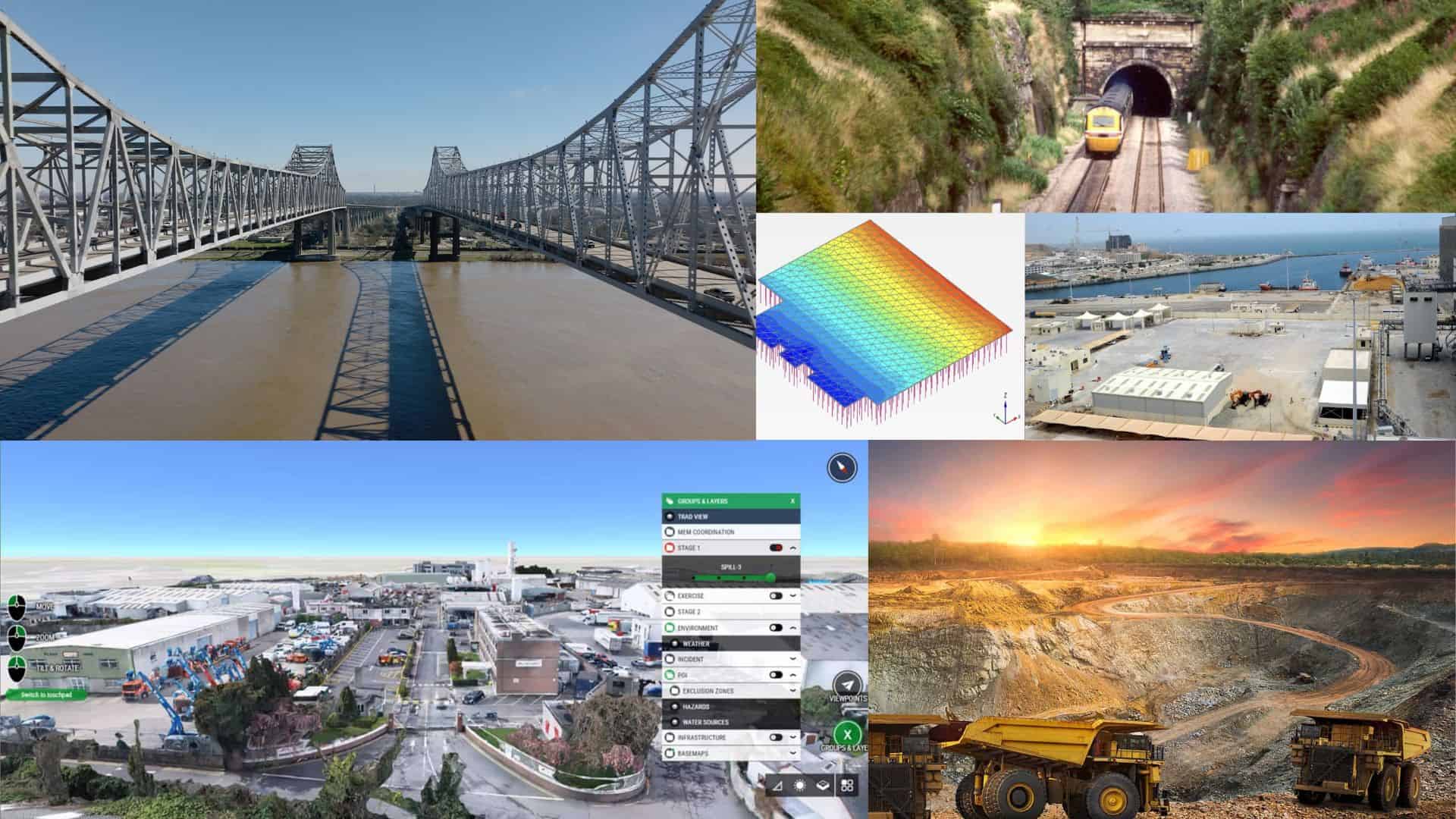

Over the last decade, digital twins have been popularized by NASA scientist John Vickers and Michael Grieves, a leading expert on the technology. The digital models are virtual replicas of a product, factory, building, supply chain, or other complex asset. Such replicas exist for jet engines, Formula 1 cars, warehouses with robots, and many other assets – but the infrastructure sector is taking the technology to a new level. Digital twins of railroads, highways, bridges, dams, energy systems, and even cities now exist, enhanced with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. The digital replicas allow architects, engineers, contractors, and infrastructure owners to query, analyze and visualize data by bringing together information that was previously locked in silos or incompatible data formats.

Digital twins are used to improve communication and collaboration among teams, optimize new designs for sustainability, or simulate different climate scenarios to improve resilience. They can even be used to monitor the condition and health of existing assets and initiate preventive maintenance.

Digital twins also use AI. For example, Bentley has been using computer vision and AI to analyze photos and videos of infrastructure projects. The technology can also build point clouds to detect cracks, rust, and vegetation. The company is now studying ways to use generative AI for design work.

Julien Moutte, Bentley’s chief technology officer, says: “We are leveraging computer vision and generative AI capabilities through infrastructure digital twins to address resource constraints, meet sustainable development goals, make assets more resilient, and overcome the challenges of today – and tomorrow.”